Translate this page into:

A Case of Lennox–Gastaut Syndrome in a 6-Year-Old Child with Moyamoya Disease

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Sir,

Lennox–Gastaut syndrome (LGS) is an age-dependent epileptic encephalopathy that often occurs secondary to perinatal insult. Seizure control and cognitive functions are often disappointing in children with LGS.[1] We report a 6-year-old boy who presented with complaints of the paucity of movement of the right side of the body since 2½ years of age and multiple episodes of convulsions since 3 years of age. He was apparently well till 2½ years of age when he developed insidious onset of weakness involving right upper and lower limb. At the age of 3 years, he developed a cluster of flexor spasms on awakening from sleep. This was followed by loss of attained language and cognitive skills. By the age of 6 years, he developed multiple types of daily seizure including nocturnal tonic seizure, tonic drop attacks, and head drops. On examination, his head circumference was <−3SD. Motor examination revealed increased tone in right upper limb and lower limb, power of <3/5 MRC, brisk deep tendon reflexes, and extensor plantar response.

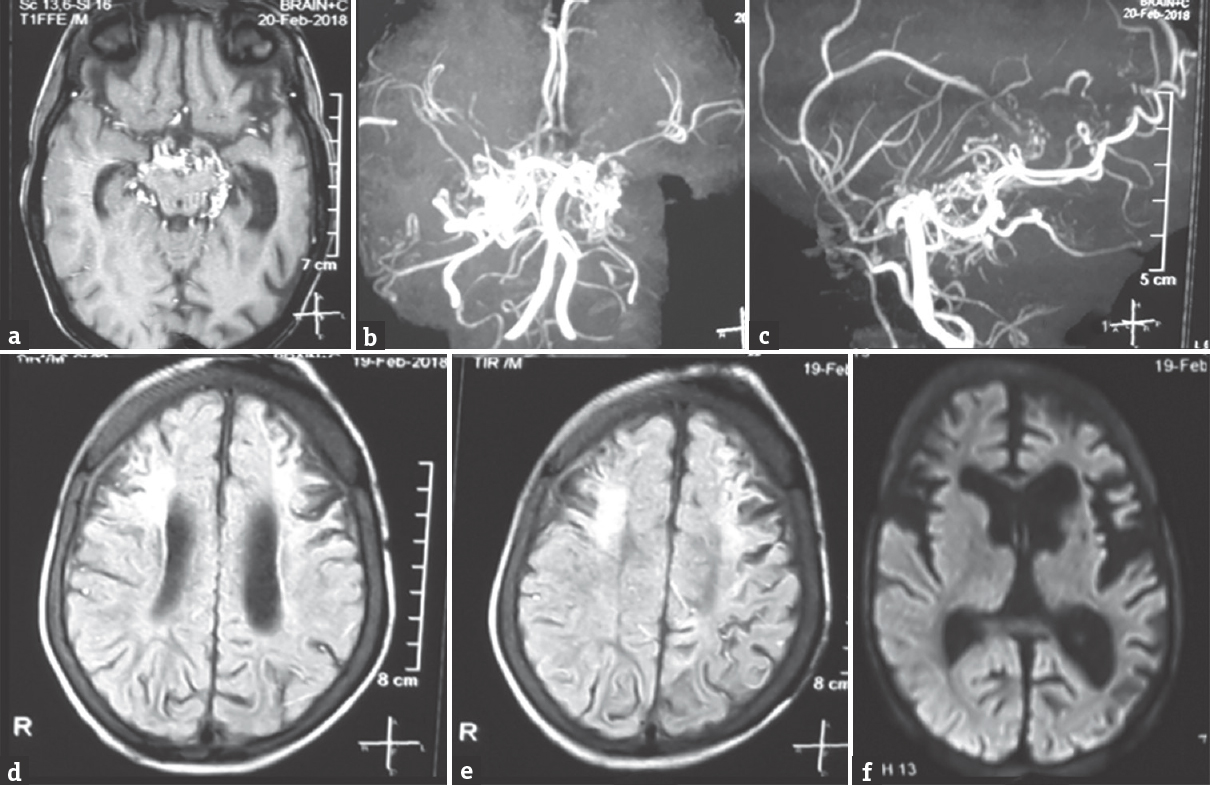

Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging brain reveals bilateral asymmetric chronic infarcts with contrast scan showing a bunch of collaterals in a basal cistern. MR angiography revealed occlusion of the bilateral distal internal carotid artery with preserved posterior circulation and dense collaterals suggestive of moyamoya disease (MMD) [Figure 1]. His electroencephalography (EEG) revealed generalized spike and slow wave complex (1–1.5 Hz, 200–300 uV) with a paucity of sleep markers and generalized paroxysmal fast activity consistent with EEG findings of LGS [Figure 2]. He was started on oral aspirin (5 mg/kg/day) with oral valproate, levetiracetam, lamotrigine, and clonazepam with seizure reduction to 1–2 episodes of tonic drop attacks. The patient is scheduled for revascularization surgery.

- Magnetic resonance imaging brain showing bilateral chronic infarcts with gliosis evident on fluid attenuation inversion recovery image (d and e) with contrast scan showing a cluster of collaterals in the basal cistern (a), with no fresh diffusion restriction (f). Magnetic resonance imaging (b and c) is showing occlusion of the bilateral terminal internal carotid artery with a tuft of collaterals at the site of stenosis giving a puff of smoke appearance

- Electroencephalography showing a burst of slow spike wave (1–1.5 Hz, 200–300 uV) followed by slowing of background. There is a generalized paroxysmal fast activity evident on the lower panel

Majority of children with LGS secondary to perinatal sequelae have poor seizure control and unfavorable neurological outcome. The present case report highlights an uncommon and surgically treatable cause of this epileptic encephalopathy. MMD is characterized by chronic progressive stenosis of a bilateral terminal portion of the internal carotid artery or proximal portion of the anterior cerebral artery and/or middle cerebral artery.[2]“Epileptic type” of MMD often manifests with focal seizure secondary to structural old infarcts with majority improving following surgical intervention.[3] The risk factors for epilepsy in MMD include early onset of seizures, onset <3 years, and presence of cortical involvement.[4] The outcome of children with MMD depends on the area of the brain involved, the severity of the vascular event, age at onset and type and success of treatment.[5]

This case highlights surgical revascularization as a possible surgical option for LGS. However, long waiting time for surgery and lack of technical expertise for surgical revascularization as in the present case are common limitations in care of children with MMD in developing countries. The present case report adds epileptic encephalopathy as a first clinical presentation of MMD. MMD may be considered as one of possible reversal cause of LGS.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Expert opinion on the management of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome: Treatment algorithms and practical considerations. Front Neurol. 2017;8:505.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis of moyamoya disease: International standard and regional differences. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2015;55:189-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-term follow-up study of “epileptic type” moyamoya disease in children. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1993;33:621-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predictive factors for epilepsy in moyamoya disease. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis J Natl Stroke Assoc. 2015;24:17-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Moyamoya disease: A review of the literature. Appl Neuropsychol Adult. 2014;21:21-7.

- [Google Scholar]