Translate this page into:

Preliminary Results of the Macedonian-Adapted Version of Ages and Stages Developmental Questionnaires

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Context:

Early detection of developmental problems is critical, and interventions are more effective when they are carried out early in a child's life. In Macedonia, there are only four centers providing early intervention services.

Aims:

In this research, we determined the reliability of the translation and adaptation of Ages and Stages Questionnaires 3rd edition (ASQ-3-M) for assessment of children aged 3–5 years old in Macedonia, and reported preliminary results of the gender differences in the development.

Materials and Methods:

ASQ-3-M was completed by 165 parents and 40 educators in seven kindergarten classrooms. Children were 3–5 years old.

Statistical Analysis Used:

Cronbach's alpha, Intraclass Correlation coefficient (ICC), and interrater reliability (IRR) were used to assess ASQ-3-M psychometric properties. The Bayesian t-test was performed to estimate the difference in means between males and females.

Results:

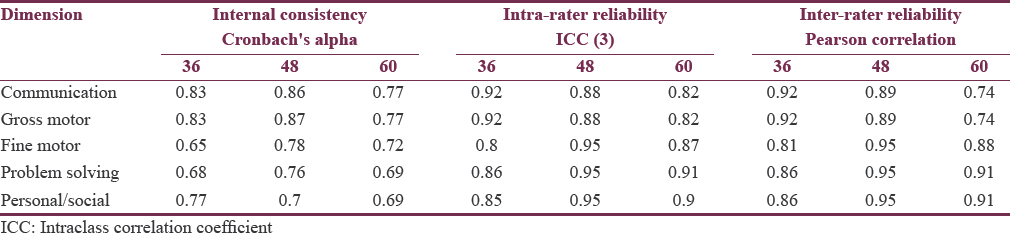

The Cronbach's alpha ranged from 0.65 to 0.87. The overall ICC was 0.89 (ranged from 0.8 to 0.95), which indicates a strong to almost perfect strength of agreement between test-retest. IRR correlation revealed an average of 0.88 (ranged from 0.74 to 0.95), suggesting that ASQ-3-M is reliable and stable.

Conclusions:

The results from the comparison between males and females on all dimensions of ASQ-3-M were not statistically significant (BF10 <3), indicating no significant gender difference. That said, the ASQ-3 is recommended for routine use in screening children aged 3–5 years old.

Keywords

Ages and stages questionnaire

Bayesian analysis

child development

developmental assessment

Macedonia

INTRODUCTION

Early experiences affect the development of the brain and have a direct impact on how children develop their sociability, self-expression, independence, initiative, and social and emotional skills.[123] Once infancy is a crucial time for both physically and mentally in every human's life, measuring the development in young children promotes information that can be used to determine which groups of children are eligible for receiving further assistance and provides the opportunity for children to benefit from early intervention.

Several approaches have been used to assess young children's developmental outcomes and the results of psychometric testing, in general, and screening tools, in specific, accurately reflect children development, when the tool administered has adequate psychometric properties. From this standpoint, psychometric instruments must guarantee their validity and reliability. Validity refers to the accuracy of measurement for a specific purpose and is the extent to which the test measures what it says it measures. Reliability refers the degree to which an assessment instrument produces stable and consistent results each time it is used in the same setting with the same type of subjects.[4]

In spite of that, there is a lack of a screening and early identification system for preschool children in the Republic of Macedonia. Children are often not identified as having disabilities until they are 3 years or older and sometimes, not even until they start school (Dimitrova-Radojichikj, Chichevska-Jovanova, and Rashikj-Canevska, 2016). This situation can be partially explained because in Macedonia, there are only four centers that provide early intervention services and because of the absence of psychometric screening tools: Even if a wide range of screening tools is available to assess child development, before a local adaptation, their use is limited to the population from whom they were developed.[5]

The process of developing, adapting, and implementing screening tools to use with Macedonian children is vital to improve services for young children and help them to reach their full potential. With that said, the purpose of this study is to verify the reliability of the translated and adapted version of Ages and Stages Questionnaires, 3rd Edition (ASQ-3-M) with data gathered in Republic of Macedonia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

This study included 165 Macedonian children at the age of 36, 48, and 60 months, their parents and their kindergarten teachers. Participants were randomly selected from 7 kindergartens in different parts in Skopje.

Measures: Ages and Stages Questionnaires, 3rd Edition

ASQ-3, was chosen as a study target because is currently the most used parent-completed developmental screener in the world[6] and has been successfully studied in different countries and cultures.[789]

The ASQ-3 consists of 21 questionnaires, for children from 2 to 66 months. Each questionnaire contains 30 questions composed by 6 questions for each domain: communication, gross motor, fine motor, problem solving, and personal-social. ASQ questions are written at the fourth to sixth grade reading level and can be administered as an interview for parents with low literacy levels and include illustrations that assist parents in understanding items. Parents indicate “yes,” “sometimes,” or “not yet” in response to each item, with point values of 10, 5, or 0, respectively.[1011]

Each domain score is independently and there are empirically derived cutoff scores to indicate whether the questionnaire falls within a normal developmental range based on chronological age, or if the score represents “at risk” or delayed development. The ASQ requires about 15 min to complete and 2–3 min to score.[12]

Children whose scores fall within the “typical” range or above the cutoff scores are considered to be developing appropriately and should continue the screening process at regular intervals. Children whose scores fall below the cut off score in any developmental area are recommended to receive further assessment. If a child's scores fall within the monitoring zone (1–2 standard deviations below the mean), specialized activities and repeat screening are recommended.[1112]

Procedures

The ASQ was translated into Macedonian (i.e., ASQ-3-M) and necessary cross-cultural adaptations were made, and then it was back translated. The accuracy of the translation was evaluated and changes were made, when necessary, by members of the research team who were very proficient in both languages.

After this, the translated version was distributed and completed by 165 parents and by 40 teachers in their seven kindergarten classrooms over a 6 months’ time period. Questionnaires were distributed to teachers and parents at the same time. A demographic form attached to the questionnaire asked for general family information on the child's gender, date of child's birth, parents’ age, education level, gender, and nationality. The researcher personally traveled to all kindergartens and had meetings with directors, teachers, and the staff to explain the study, its goals, procedures, and steps. After teachers had given permission to participate, the study was presented to parents, and they gave their permission if they were willing to participate.

When parents returned the questionnaire, they received a duplicate copy of the same ASQ-3-M corresponding to their child's age to complete. They were distributed by researcher and teacher only in hard copy (some of the questionnaires for parents were distributed via teachers to the parents). Teachers and the researcher collected the questionnaires and remained parents to complete both questionnaires throughout the process. The researcher entered all study data into a secure database.

Statistical analysis

Internal consistency reliability was assessed by calculating the Cronbach's α coefficient and results equal or above 0.7 are considered acceptable.[13] To assess test-retest reliability, the parents were asked to complete the ASQ-3-M on their child and then, to complete the same questionnaire 2 weeks apart, blind to the outcomes of the first result. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was computed with the results. An ICC between 0.75 and 0.90 indicates good test-retest reliability.[4] Interrater reliability (IRR, a.k.a., Interobserver reliability) was estimated by using Pearson Product Moment Correlation in the results from the questionnaires completed by parents and kindergarten teachers for the same children.

To investigate how much males and females’ results were different one from another in all domains of ASQ-3-M, since the small sample in this research, a Bayesian t-test was performed using with a prior width set at r = 0.707, which is recommended as the default value for this test.[14] Bayes factors provide a numerical value that quantifies how well a hypothesis predicts the empirical data relative to a competing hypothesis. The Bayes Factor (BF10) expresses the probability of the data in favor of H1 relative H0. If the BF10 is equal to 1, it indicates that the observed finding is equally likely under both hypotheses, if BF10 is >1 then the data provide support for the alternative hypothesis and if BF10 is <1 then the data provide support for the null hypothesis.[1415]

The significance threshold for Bayesian inference was set at BF10 >3 and for frequentist inference was set at P < 0.05. There was no missing value in dataset and data were analyzed by using R statistical software version 3.4.4[16] with tidyverse, BayesFactor[17] and psych[18] packages.

RESULTS

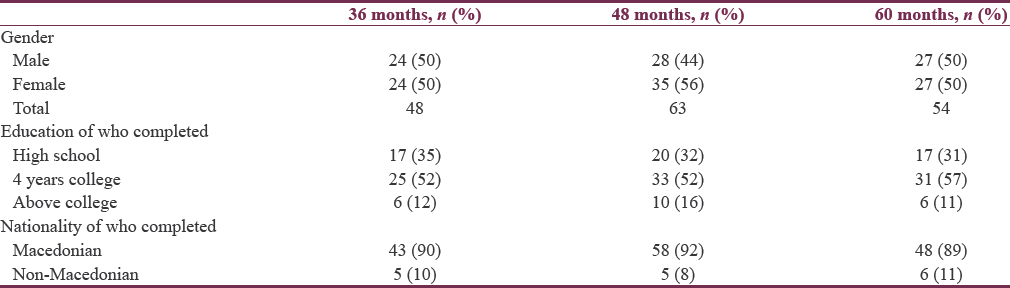

Of the 210 participants’ approaches to take part in this study, 165 (78.6%) completed the ASQ: 3-M. These results are presented in Table 1, which show the absolute frequency and percentage of each included sociodemographic variable.

The reliability was estimated by three different ways: Internal consistency with Cronbach's alpha, test-retest reliability by ICC and IRR by Pearson Product-Moment correlation. All results were significant, and the outcomes are reported in Table 2.

Cronbach alpha is a test of internal consistency and the higher is the score, the better is the internal consistency. Test-retest provides clinicians with the assurance that the instrument measures the outcome the same way each time it is performed. Better reproducibility, measured by higher ICC, suggests better precision of single measurements, which is a requirement for better tracking of changes in measurement. IRR assess the degree to which different raters/observers give consistent estimates of the same phenomenon.

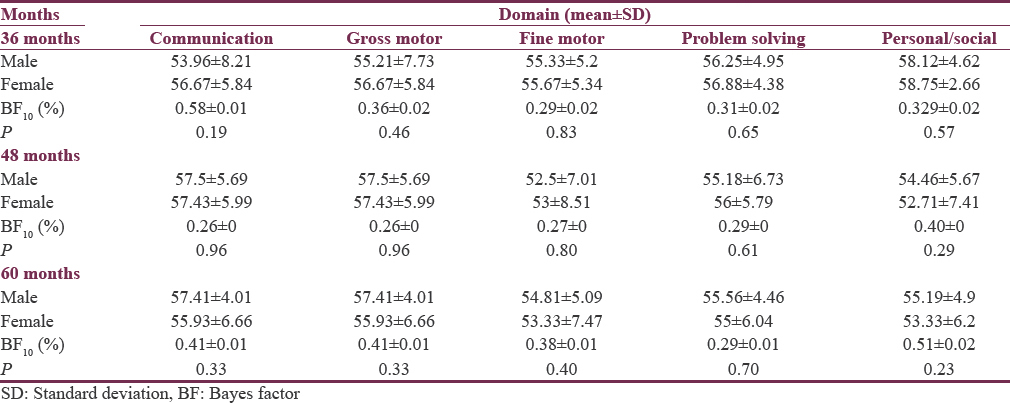

To decide which of two hypotheses is more likely given an experimental result, one must consider the ratios of their likelihoods. This ratio is called the Bayes Factor (BF), and BF10 reflects the likelihood of H1 compared to H0 given a set of data. BF is a continuous measure of evidence and results with values between 1 and 3 are seems as inconclusive, values between 3 and 10 are weak and >10 are generally seem as strong evidence. Results are reported in Table 3.

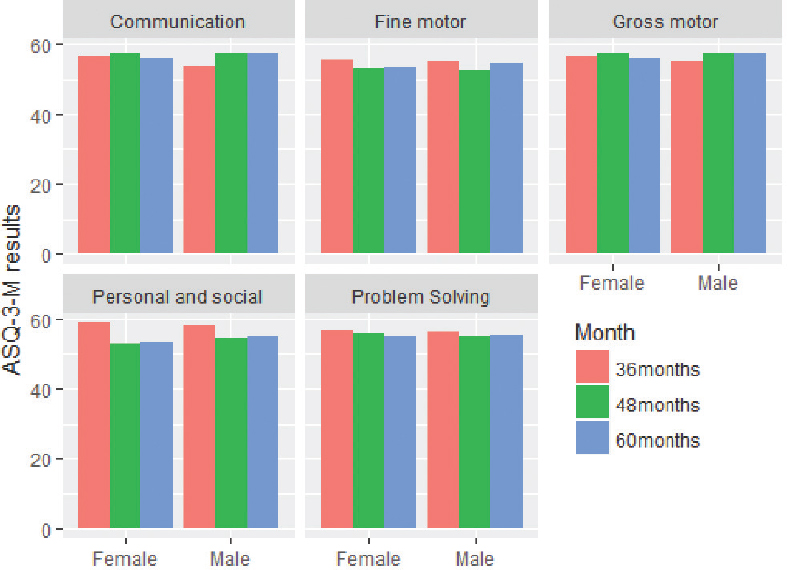

Despite the numerical difference, there were no evidence of a statistically difference between males and females in terms of their abilities. Figure 1 displays the mean scores of all vb ariables of ASQ-3-M for males and females.

- Gender differences (Bayes t-test)

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study of the Macedonian version of ASQ-3, as well the first to investigate the gender differences in response to it. In terms of cultural and linguistic appropriateness for Macedonian children, some items underwent modifications to ensure words and phrases are semantically similar, with a minimum of wording changes. A similar process of item adaptation happened in other countries, such as Brazil,[7] Chile,[8] and China,[9] which points to the importance of the cross-cultural adaptation of psychological instruments before its implementation.[5]

The internal consistency of the questionnaire ranged between 0.65 and 0.87. These results were higher than studies in Portugal,[19] but were similar to other international studies, such as those conducted in China[9] and in Arabic countries.[20] This outcome indicates that although some items were changed, they retained their concepts and did not lose their original meanings. Test-retest reliability measures the stability of test outcomes over time and was estimated by having parents complete two ASQ-3-M’ on the same child within a 2 weeks’ interval. The ICC between scores of the two ASQ-3-M concludes the stability of the scores of ASQ-3-M. Similar findings were found in other studies.[1021]

The IRR refers to the agreement of test outcomes and was examined using Person Product Moment. The results between parents and kind garden teachers were lower than the original ASQ-3 study,[12] but showed a strong agreement between both parents and teachers. The literature about the agreement between professionals and parents led both results (high and low agreement) and this evidence and this results provides supporting to evidence of the agreement regarding child development.[22]

There were no significant differences between the groups with respect to all scales of ASQ-3-M. However, although these results did not show a statistically significant difference between genders on any of the ASQ-3-M domains, this could be seen as result of having small sample. Variations between men and women development can be found in the literature[12] and in other studies that used ASQ-3 was measurement tool.[2324]

Some limitations are presented in these results. This study included only children at preschool age (36, 48, and 60 months) and only in Skopje. For a valid normative study, a larger sample of at least 100 children at each age interval is needed, stratified on a national Macedonia sample. In addition, only paper questionnaires were used in this study and to truly reach diverse young children; an online system would be preferable, as this would reduce the time and energy needed for data collection in individual kindergarten classrooms throughout the country. However, the impact of the limitations was small, as can be seen in the findings of this study.

These issues aside, as mentioned earlier, the basis of adult health and well-being are built prenatally and during early childhood.[1325] The availability of ASQ: 3-M opens up possibilities for examining child development in diverse cultural groups, as well as for effective cross-cultural comparisons of development.

It was concluded that the Macedonian version of the ASQ-3 questionnaire was successfully translated and adapted, with good internal consistency and reliability, which provide solid support for the use of the scale to measure domains of child development among children in Macedonia. While this study has demonstrated the potential ASQ-3-M, it also being extended in longitudinal and comparative ways.

Financial support and sponsorship

Authors would like to say thanks to “Singh & Yeh Foundation, USA” for partial financial support to this research study.

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Squires is an author of the ASQ and receives some royalties from its publication.

REFERENCES

- Early adverse experiences and the developing brain. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41:177-96.

- [Google Scholar]

- Examining the psychometric properties of the Brazilian ages & stages questionnaires-social-emotional: Use in public child daycare centers in Brazil. 2017. Child Fam Stud. 26:2412-25. Available from: http://www.link.springer.com/10.1007/s10826-017-0770-0

- [Google Scholar]

- The importance of early bonding on the long-term mental health and resilience of children. London J Prim Care (Abingdon). 2016;8:12-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- A primer on the validity of assessment instruments. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3:119-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Child development assessment tools in low-income and middle-income countries: How can we use them more appropriately? Arch Dis Child. 2015;100:482-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Validity and internal consistency of the ages and stages questionnaire 60-month version and the effect of three scoring methods. Early Hum Dev. 2013;89:1011-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychometric properties of the Brazilian-adapted version of the ages and stages questionnaire in public child daycare centers. Early Hum Dev. 2013;89:561-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- Validation of the chilean version of the ages and stages questionnaire (ASQ-CL) in community health settings. Early Hum Dev. 2015;91:671-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Translation and use of parent-completed developmental screening test in Shanghai. 2012. Early Child Res. 10:162-75. Available from: http://www.journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1476718X11430071

- [Google Scholar]

- Validity and reliability of the developmental assessment screening scale. J Family Med Prim Care. 2016;5:124-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of implementing developmental screening at 12 and 24 months in a pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2007;120:381-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ages & Stages Questionnaires. 2009. (ASQ-3[TM]): A Parent-Completed Child-Monitoring System. (3rd ed). Brookes Publishing Company; Available from: http://www.search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eric&AN=ED507532&site=ehost-live&scope=site%5Cnhttp://www.brookespublishing.com/store/books/squires-asq/index.htm

- [Google Scholar]

- Research Methods in Health Investigating Health and Health Services. Buckingham: Public Health; 2009. p. :1-525.

- Bayesian inference for psychology. Part II: Example applications with JASP. Psychon Bull Rev. 2018;25:58-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- A test by any other name:P Values, bayes factors, and statistical inference. Multivariate Behav Res. 2016;51:23-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2017. R Development Core Team [Internet]. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available from: http://www.r.project.org

- Default bayes factors for ANOVA designs. 2012. Math Psychol. 56:356-74. Available from: http://www.linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0022249612000806

- [Google Scholar]

- Procedures for Personality and Psychological Research, Northwestern University. 2018. Evanston, Illinois: USA; Available from: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychometric properties and validation of portuguese version of ages & stages questionnaires (3rd edition): 9, 18 and 30 questionnaires. Early Hum Dev. 2015;91:527-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cross-cultural adaptation, validation and standardization of ages and stages questionnaire (ASQ) in Iranian children. Iran J Public Health. 2013;42:522-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Studies of the norm and psychometrical properties of the ages and stages questionnaires, third edition, with a Chinese national sample. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2015;53:913-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Parent-teacher agreement on children's problems in 21 societies. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2014;43:627-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cultural adaptation and psychometric validation of the ages and stages questionnaires for use in Georgia. 2017. Child Fam Stud. 27:739-749. Available from: http://www.link.springer.com/10.1007/s10826-017-0917-z

- [Google Scholar]

- The developmental relationship between language and motor performance from 3 to 5 years of age: a prospective longitudinal population study. 2014. BMC Psychol. 2:34. Available from: http://www.bmcpsychology.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40359-014-0034-3

- [Google Scholar]

- Toward understanding how early-life stress reprograms cognitive and emotional brain networks. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41:197-206.

- [Google Scholar]