Translate this page into:

Preeruptive Unilateral Cerebellar Ataxia in an Immunocompetent Adult: A Rare Case of Varicella

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Sir,

Varicella is an acute exanthematous, highly contagious disease caused by varicella-zoster virus (VZV). Neurological complications are the second most common complication in 0.1%–0.75% of cases following secondary bacterial infection of the skin lesion.[1] The neurological complications include acute cerebellar ataxia, meningitis, encephalitis, stroke or stroke-like episodes, myelitis, and vasculopathy.[2] There are numerous evidence and reports on VZV cerebellitis mainly in childhood including preeruptive cerebellitis. However, the incidence in adult is rather uncommon.

A 23-year-old woman with no known medical illness, presented with a 1-week history of unsteady gait and slurring of speech. This was the first episode, and it progressively worsened over the subsequent days. She had no history of fever, headache, or limb weakness. There was no history of exposure to chickenpox or past VZV vaccination. She was not on any medication and did not consume alcohol or smoke.

On physical examination, she was alert, orientated, and afebrile. The neck was supple, and there was no rash on skin examination. Neurological examinations showed dysdiadochokinesia, impaired finger–nose testing with dysmetria and intentional tremor on the left upper limb, and impaired heel–shin test on the left lower limb. There was left horizontal nystagmus with the fast component to the left side. Her gait was ataxic with a tendency to fall to the left. She had a staccato speech. There was no relative afferent pupillary defect, pyramidal tract sign, or peripheral neuropathy.

Laboratory analysis revealed values within normal ranges for hemoglobin (14.5 g/dL) and platelet (405 x 109/L); an elevated white blood cells count (11.9 x 109/L); 60% neutrophils, 29% lymphocytes, 1.7% eosinophils, 7.5% monocytes, and 0.5% basophils), normal electrolytes, thyroid, renal, and liver function. Infective screenings for hepatitis B, hepatitis C, HIV, and venereal disease research laboratory for syphilis were nonreactive and antinuclear antibody was negative. Lumbar puncture was subsequently done and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis revealed normal protein (0.38 g/L) and glucose (3.4 mmol/L, 72% to random blood sugar), normal microscopic examination and zero cell count, negative Gram stain, acid–fast bacilli stain and Indian ink, and negative pathogen culture. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)/magnetic resonance angiogram of the brain was normal.

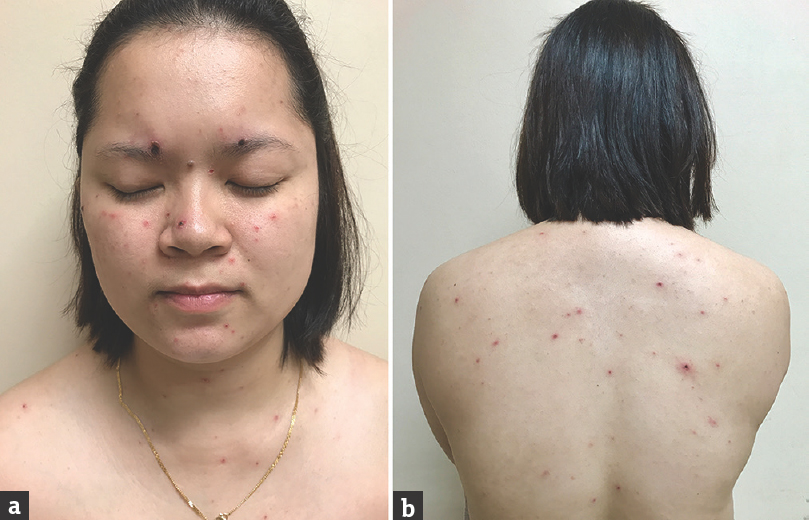

The patient was treated as left cerebellitis with intravenous methylprednisolone 1 g daily for 3 days. Four weeks following the initial presentation, she was noted to have eruption of chickenpox. There were multiple varying ages of vesicles, crusted papules, and pustules over the face, trunk, and sparsely limbs [Figure 1]. She still had significant neurological signs at this stage with left dysdiadochokinesia and impaired finger–nose testing. Her gait was still ataxic which required support for the ambulation. Serum varicella-zoster IgG and IgM were positive. She was given a week course of oral acyclovir 800 mg five times a day. She was reviewed at 2-month follow-up, and her neurological signs had resolved except very mild left upper limb ataxia with no functional limitation.

- Day 3 of chickenpox eruption with varying ages of vesicles, crusted papules, and pustules mainly over face (a) and trunk (b)

VZV infection is usually a self-limiting childhood disease. However, the disease can be associated with potentially lethal complication in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised person. There are various neurological complications either caused by a primary infection or viral reactivation. Acute cerebellar ataxia is the most common neurological complication in children, occurring at 4%–8% of those hospitalized for varicella.[3] Whereas in adult, encephalitis and meningitis are more common and mostly caused by reactivated VZV and frequently detached among elderly and immunocompromised patient.[456]

There are different clinical symptoms in acute cerebellar ataxia and the most characteristic symptom observed by Bozzola et al. was broad-based gait disturbance, which progressed over the course of a few days (95.8%). Other common symptoms included slurred speech (37.5%), vomiting (31.25%), headache (29.16%), dysmetria (25%), and tremor (22.91%).[3]

Preeruptive, acute cerebellar ataxia in varicella is very rare and may pose diagnostic dilemma for clinicians. Reports of patients presented with acute cerebellar ataxia during preeruptive phase of varicella are summarized in Table 1. All the published reports described the phenomenon in childhood, and it is noteworthy that almost all were male patients. The interval between the onset of cerebellar ataxia and development of rash was variable, up to 19 days as reported by Takeuchi et al.[10] Our present patient represented the most unusual one, occurring in adulthood, female, and had the longest preeruptive phase of 28 days. Interestingly to date, there are four recognized cases of virologically confirmed VZV cerebellitis without skin manifestation in adult.[15161718] However, all of them received intravenous acyclovir, and the underlying pathogenesis could be due to viral reactivation rather than primary varicella infection. It is, therefore, possible that typical eruptive phase did not occur.

The pathogenesis of neurological complications in varicella was not clearly defined. It is postulated that the preeruptive neurological symptoms are due to direct viral invasion of the central nervous system, whereas the symptoms occurring after the eruptive phase may be the result of postinfectious autoimmune process.[91012] The unilateral clinical presentation of the case showed that the pathology is not always bilateral.

CSF analysis in VZV cerebellitis usually showed normal or raised opening pressure, slightly raised cell count, normal or raised protein, and sugar.[8] CSF/serum VZV antibody ratio and CSF VZV-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis are particularly useful for earlier diagnosis. However, a normal VZV antibody titer and CSF/serum antibody ratio at onset do not exclude VZV-associated neurological involvement as it usually rises 1–2 weeks after the onset of disease.[15] Similarly, the absence of detectable VZV DNA in CSF does not preclude the diagnosis as its sensitivity to nonmeningeal disease may be low.[19] MRI brain is superior to computed tomography brain, and the most common finding is bilateral diffuse abnormalities of the cerebellar hemispheres.[20] However, neuroimaging in VZV cerebellitis is often normal, and there is no pathognomonic feature.

Treatment with antiviral was considered mandatory in a recent article for patients at risk of severe disease, and any patient with VZV infection with virally mediated complication.[21] The prognosis of VZV cerebellitis is generally favorable with very low mortality and recovery is a norm.[81314] However, most of the evidences are from children and data for adult is lacking and unclear.

It was recognized that CSF VZV antibody and CSF PCR for VZV DNA were not obtained in the present patient to support the diagnosis. However, judging from the clinical course and having ruled out all the other possible causes, the diagnosis of preeruptive cerebellar ataxia in varicella was concluded.

Preeruptive cerebellar ataxia in varicella is very rare, especially in adults. Clinicians dealing with cerebellar syndrome should always consider and investigate the possibility of VZV infection even without typical exanthematous rash. Early diagnosis may prevent unnecessary procedure and reduce the morbidity and mortality. This is the first case reported in an immunocompetent adult, with the longest duration of preeruptive period.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- CNS diseases associated with varicella zoster virus and herpes simplex virus infection.Pathogenesis and current therapy. Neurol Clin. 1986;4:265-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- Neurological complications of varicella in childhood: Case series and a systematic review of the literature. Vaccine. 2012;30:5785-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute cerebellitis in varicella: A ten year case series and systematic review of the literature. Ital J Pediatr. 2014;40:57.

- [Google Scholar]

- Varicella-zoster virus infections of the central nervous system – Prognosis, diagnostics and treatment. J Infect. 2015;71:281-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Neurological complications due to chicken pox in adults: A retrospective study of 20 patients. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2016;19:161-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- The neurological complications of varicella.A clinical and epidemiological study. Br J Child Dis. 1935;32:83-107. 177-9, 241-63

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute cerebellar ataxia of childhood.An unusual case of varicella. West J Med. 1974;120:161-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recurrent and pre-eruptive acute cerebellar ataxia: A rare case of varicella. Pediatr Neurol. 1987;3:240-1.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pre-eruptive varicella encephalitis and cerebellar ataxia. Pediatr Neurol. 1992;8:69-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pre-eruptive varicella cerebellitis confirmed by PCR. Pediatr Neurol. 1993;9:491-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Varicella zoster virus cerebellitis in a 66-year-old patient without herpes zoster. Lancet. 2006;367:182.

- [Google Scholar]

- Case of acute cerebellitis as a result of varicella zoster virus infection without skin manifestations. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2012;12:756-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Varicella zoster virus cerebellitis without a rash in an immunocompetent 85-year-old patient. Neurologist. 2015;20:44-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Central nervous system complications of varicella-zoster virus. J Pediatr. 2014;165:779-85.

- [Google Scholar]