Translate this page into:

Psychiatric Presentations Heralding Hashimoto's Encephalopathy: A Systematic Review and Analysis of Cases Reported in Literature

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Hashimoto's encephalopathy (HE) may often present initially with psychiatric symptoms. These presentations are often variable in clinical aspects, and there has been no systematic analysis of the numerous psychiatric presentations heralding an eventual diagnosis of HE which will guide clinicians to make a correct diagnosis of HE. This systematic review was done to analyze the demographic characteristics, symptom typology, and clinical and treatment variables associated with such forerunner presentations. Electronic databases such as PubMed, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar databases were searched to identify potential case reports that described initial psychiatric presentations of HE in English language peer-reviewed journals. The generated articles were evaluated and relevant data were extracted using a structured tool. We identified a total of forty articles that described 46 cases. More than half of the total samples (54.4%) were above the age of 50 years at presentation. The most common psychiatric diagnosis heralding HE was acute psychosis (26.1%) followed by depressive disorders (23.9%). Dementia (10.9%) and schizophrenia (2.2%) were uncommon presentations. Antithyroid peroxidase antibodies were elevated in all patients but not antithyroglobulin antibodies. Preexisting hypothyroidism was absent in majority of cases (60.9%). Steroid doses initiated were 500–1000 mg of intravenous methylprednisolone for majority (52.1%) of patients while oral steroid maintenance was required for a significant minority (39.1%). Psychiatric manifestations of HE may be heterogeneous and require a high index of clinical suspicion, especially in older adults. A range of clinical and treatment variables may assist clinicians in making a faster diagnosis and instituting prompt and effective management.

Keywords

Acute psychosis

Hashimoto's disease

Hashimoto's encephalopathy

Hashimoto's thyroiditis

psychiatry

INTRODUCTION

Hashimoto's encephalopathy (HE), known eponymously as steroid-responsive encephalopathy associated with autoimmune thyroiditis, is an uncommon, poorly understood, and often misdiagnosed neuropsychiatric condition.[1] The term, first used by Shaw et al. in 1991, broadly subsumes patients who present with varied signs of encephalopathy coupled with elevated levels of thyroid antibodies and good, often dramatic, response to corticosteroid therapy.[2] The first probable case of Hashimoto's disease manifesting with tremors, change in consciousness, cognition and stroke-like episodes was described by Brain et al. in 1966[3] and since then many reports have emerged that highlight the protean neuropsychiatric manifestations of this intriguing condition.[456]

The pathogenesis of the condition remains poorly understood. Specifically, it has been observed that while nearly all patients with HE demonstrate elevated levels of antithyroid antibodies,[78] a causal or linear relationship between antibody titers and HE has not been established. Other factors thought to play a crucial role in pathogenesis of HE include impairments in cerebral perfusion and metabolism owing to diffuse vasculitis and/or disseminated encephalomyelitis.[910] This, in turn, gives rise to broad spectrum of multifocal deficits that are difficult to capture through rigid diagnostic criteria. Fortunately, there are no such challenges on the treatment side as the condition traditionally responds well to steroid therapy.[4] Early recognition of the syndrome remains an important unmet need in HE. Currently, there are no recognized or universally accepted criteria to aid clinicians in making a diagnosis of HE.

In such a scenario, physicians have to rely on clinical observations in the form of case reports/series/analytical synthesis of cases reported in literature to delineate common presentations of this condition. Psychiatric presentations constitute a significant proportion of HE.[11] Although many cases of HE with initial psychiatric presentation have been reported in literature, they vary in their demographic, clinical, and treatment characteristics. We could not identify any systematic review that summarizes the evidence in this regard. To bridge this knowledge gap, we undertook the present review with the objective of examining the demographic, clinical, and treatment-related factors of HE cases reported in literature, focusing on those reports where psychiatric manifestations have heralded the eventual diagnosis of HE.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search strategy and study selection

Electronic searches of PubMed, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar databases were carried out with the aim of identifying published case reports describing preliminary psychiatric presentations of HE. The search was done using the following subject headings or free text terms: HE, Hashimoto's thyroiditis, Hashimoto's disease, steroid responsive encephalopathy, hypothyroidism, and autoimmune thyroiditis. The searches were carried out in July 2016 and were independently performed by the two authors who were both qualified psychiatrists (Vikas Menon and Jaiganesh Selvapandian Thamizh). The search filter of “case report” was not used as many case reports are increasingly being published as letters to the editor. The search results of the two authors were compared and after weeding out duplicate articles, a consolidated list of abstracts was drawn up. Next, a supplemental Google search using random combinations of the above terms was done to further screen the available literature. Cross-references of selected papers were also screened to identify relevant articles. The search was restricted to articles in the English language without any restriction on the date of publication. We included reports that described pure psychiatric or mixed presentations (e.g., psychiatric and neurologic) of HE as the latter presentations may often come first to a psychiatrist. Any disagreement was sorted out through mutual discussion and consensus. We did not include unpublished material or those not available in peer-reviewed journals (e.g., conference presentations) as they were not readily accessible. We did not contact authors for further information and relied solely on electronic material available. Comprehensive hand-searches of the physical library were not carried out as part of the present review.

Data extraction

The full texts of the relevant articles were used to extract information about relevant demographic variables such as age, gender, and country of residence. Clinical and treatment related information such as typology of psychiatric manifestation (affective illness/psychotic illness etc.), levels of antithyroid antibodies, duration of hypothyroidism (if diagnosed earlier), adequacy of replacement therapy, name and dosages of psychopharmacologic agents, any special treatments used such as electroconvulsive therapy, dose of corticosteroid employed, and time course of response was also gathered. Data extraction was done by two of the authors (Vikas Menon and Karthick Subramanian).

Data analysis

Descriptive analysis was used to depict the data collected. Demographic and clinical variables were expressed as simple frequencies and percentages. We focused on the summary numbers in each category. Inferential statistics were not required. As the review included only individual case reports, we could not calculate effect sizes. For the same reason, we also did not assess the quality of data collected.

RESULTS

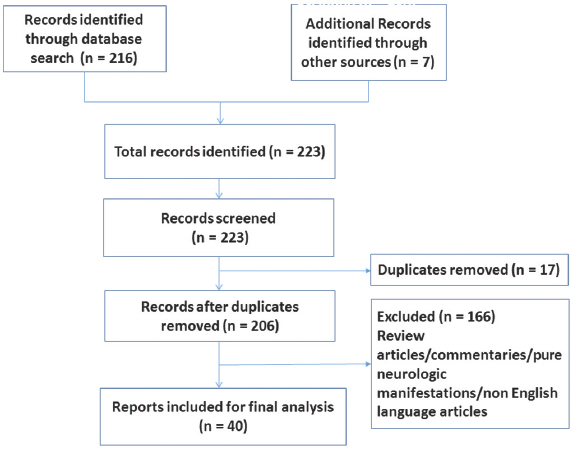

The flowchart depicting the results of the literature search is shown in Figure 1. The majority (n = 27, 67.5%) of the case reports/series were published after 2010[121314151617181920212223242526272829303132333435363738] perhaps indicating an increased awareness of the protean manifestations of HE. After following the inclusion and exclusion criteria and removing duplicates, a total of forty articles describing 46 cases were identified. These reports varyingly described one,[12141517181920212223242526272829303133343536383940414243444546474849] two,[323750] or a maximum of three cases.[1316] Table 1 summarizes the age and gender distribution of the cases included for review. The age range of the sample was 14–84 years. The mean age was 50.3 (±19.1) years. More than a third of the sample (n = 16, 34.8%) was above 60 years of age at index presentation. Only nine of the reported cases (19.15%) described male patients with psychiatric presentations of HE.[131621252731343948]

- Flowchart for literature search

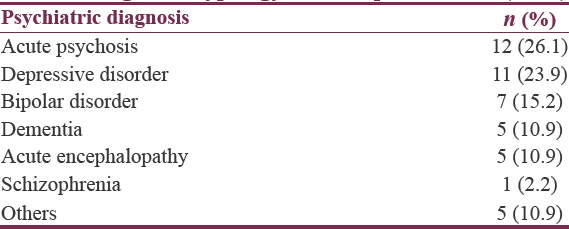

The diagnostic typology of the index presentation is depicted in Table 2. The most common psychiatric presentation heralding HE was acute psychosis (26.1%),[161721222526283839444548] followed by depressive disorder (23.9%),[1213151619313435374750] bipolar disorder (15.2%),[13142930404350] dementia (10.9%),[1827374146] and acute encephalopathy (10.9%).[13163249] A diagnosis of schizophrenia was made in one case.[42] Five reports described patients with paroxysmal nocturnal amnesia,[33] mixed anxiety-depression,[36] vitamin B12-related neuroanemic syndrome,[24] generalized anxiety disorder,[20] and conversion disorder,[23] respectively.

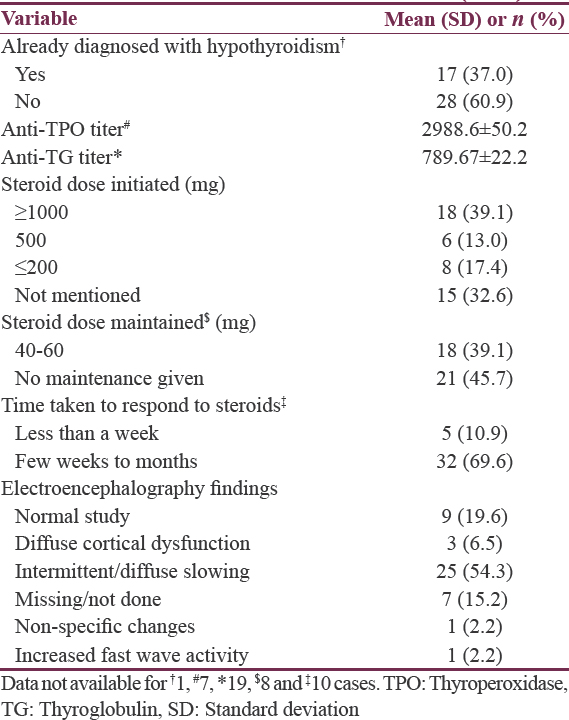

The relevant clinical and treatment variables are summarized in Table 3. The majority of the sample (n = 28,60.9%) had not been diagnosed with hypothyroidism.[1213141617192025262728323436394142434647484950] In four cases, the antithyroglobulin (TG) titer was within normal limits,[32404950] but wherever the antithyroperoxidase (TPO) titer was available, it was noted to be elevated. Overall, the mean anti-TPO titers were also much higher than anti-TG titers. The steroid dose (intravenous methylprednisolone) initiated were above 500 mg for more than half the cases (n = 24.52.1%).[1213141617192122232427283132334245474950] Further, a significant minority of cases required oral maintenance steroid regimens (n = 18.39.1%) followed by gradual tapering.[1215181923242628313334384546474950] Most patients (n = 32.69.6%) required a few weeks to months for complete response. In one case, the authors have reported that it required 3 years of steroid maintenance therapy to induce clinical response.[16]

The electroencephalographic findings showed a normal record in nine patients (19.6%)[1719202335374647] while the most common abnormality noted was an intermittent or diffuse background slowing mostly in the frontal and temporal leads with or without bursts of sharp wave discharge (n = 25.54.3%).[12131416182024262728323334363941424344454950]

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) returned normal study in 26 patients (56.5%).[14151617202123242526272831323637383941424344464850] Of the others whose imaging data were available, the single most common abnormality reported were nonspecific white matter hyperintense lesions (n = 9.19.6%).[12131932354749] Functional neuroimaging imaging data (single photon emission computed tomography [SPECT]) were available for seven cases and while one of them was within normal limits,[26] the others demonstrated global cerebral hypoperfusion as well as perfusion asymmetry.[154041454748] Cerebrospinal fluid analysis (CSF) results were available for 28 out of the 46 cases. The most common anomaly reported in CSF was elevated proteins indicating a disturbance in the blood brain barrier (n = 15, 32.6%).[121316181927323641464950] While five cases tested positive for antithyroid antibodies in CSF,[1420233137] one report identified no antithyroid antibodies when specifically tested for it.[32] CSF analysis was normal in eight patients.[2226283843444547] In four cases, where a detailed analysis of antibody profile, including antinuclear antibodies, anti-double-stranded DNA, anti-Sjogren syndrome-related antigen A and B and anticardiolipin antibodies was done, all the tested antibodies were found to be within normal limits.[23313246] High serum levels of IgG were found in one patient[31] while two patients tested positive for antimicrosomal antibodies, respectively.[1844]

DISCUSSION

The majority of the reported cases in the present systematic review involved females and aged above 50 years. This evidence converges with extant literature that shows a female preponderance in HE with a male to female ratio of around 1:5. This gender difference has been explained based on sex differences in immune response, reproductive ability, sex hormones, and epigenetic factors.[5152] Although the mean age of onset of HE has been noted to be approximately 45–55 years,[53] the advanced age of HE presentation noted here may indicate a missed diagnosis earlier. Hence, it is advisable to keep a high index of suspicion for HE for any patient having atypical age of onset of psychiatric symptoms.

Index psychiatric presentations of HE varied widely in the reviewed cases. Acute psychotic presentations dominated the forerunning psychiatric presentations of HE followed closely by depressive disorders and together they constituted half of the psychiatric diagnoses made at index presentation. Although prior reviews exclusively focusing on psychiatric presentations are not available, hallucinations and psychotic symptoms have been noted to be among the most common neuropsychiatric manifestations of HE.[6] Broadly, two subtypes of HE has been proposed based on presenting signs: an acute onset subtype characterized mainly by repeated episodes of stroke, seizures, and psychosis or a more indolent variety characterized by depressive features, cognitive impairment, deficits in sensorium and neurological manifestations such as tremors and myoclonus among others.[5354] Psychiatric symptoms are common for both these subtypes, and therefore, clinicians should be aware of the variety of initial psychiatric presentations of HE so as to facilitate early diagnosis.

The pathogenesis of HE is still unclear, and little is known about the role played by antithyroid antibodies toward causation. We noticed that antithyroid peroxidase antibodies were elevated in all cases where data was available. Mixed results were obtained for anti-TG antibodies with normal levels in a handful of HE patients. Raised antithyroid antibodies, particularly antithyroid peroxidase antibodies, have been found to be near ubiquitous in HE patients[5556] and therefore included in early diagnostic criteria such as those by Peschen-Rosin et al. for HE.[57] However, they are also seen in many euthyroid patients.[58] The antibody titers have not been found to correlate with clinical severity of encephalopathy in HE.[59] Hence, a direct causal relationship seems unlikely. On the other hand, based on work in monozygotic twins discordant for HE, researchers have shown that the heritability of these thyroid antibodies may render them valuable screening tools to predict evolution of HE.[60] Several mechanisms such as autoimmune vasculitis, autoantibodies against brain-thyroid antigens and encephalomyelitis associated demyelination have been proposed for HE.[6162] This raises questions about whether HE is just a part of a generalized multisystem autoimmune dysfunction than a single disorder. Based on current evidence, it appears that diffuse cerebral vasculitis and autoimmunity directed against common brain-thyroid antigens may represent the most likely etiologic pathway leading to impairments in cerebral perfusion, metabolism and/or disseminated encephalomyelitis.

Most of our sample did not have co-existent hypothyroidism. The thyroid function in HE can span the entire spectrum of overt hypothyroidism (20%), subclinical hypothyroidism (35%), euthyroid (30%) or rarely even hyperthyroidism (7%).[63] Euthyroid HE is known to progress to hypothyroid HE, and hence, it is possible that many of our patients were in the early stages of the disorder though the factors influencing progression to an eventual hypothyroid state remain unclear.[64]

Electroencephalography (EEG) showed a normal record in about one-fifths of the cases reviewed. The most common abnormality was background slowing in frontotemporal leads with intermittent sharp wave discharges. The electroencephalographic findings in HE can be as heterogeneous as the clinical presentation itself. Our findings concur with available literature in this area that mentions diffuse or rhythmic slowing as most frequently documented anomaly in the EEG.[65] Other abnormalities documented include frontal intermittent rhythmic delta activity,[66] periodic sharp waves or epileptiform discharges, photomyogenic response, and photoparoxysmal response.[6768] The background slowing on EEG may often be a reflection of the severity of underlying encephalopathy. In a prior review of adult patients with steroid-responsive encephalopathy associated with autoimmune thyroiditis, all cases reviewed showed some degree of generalized slowing, and these changes often reversed with successful treatment.[68] Henchey et al. mention that nonspecific EEG abnormalities are seen in 90%–98% of HE patients but our review suggests a slightly lower percentage (80% with abnormal EEG).[69]

MRI either returned a normal study (56.5%) or most commonly showed nonspecific focal or diffuse white matter hyperintensities. This resonates with figures quoted earlier, and the overall consensus is that MRI findings may not have diagnostic specificity for HE and other causes need to be ruled out.[5366] Apart from subcortical hyperintensities, other findings in literature include cerebral atrophy or rarely focal cortical abnormalities that often reverse with treatment.[7071] Functional imaging data were available for only a few cases and mostly showed widespread hypometabolism. Nonspecific patterns of diffuse or patchy hypoperfusion have been consistently shown in HE and appear not to correlate with clinical presentation.[404172] Brain hypoperfusion detected in SPECT supports the vasculitic model of pathogenesis in HE. CSF analysis was normal in 28.5% of patients with available data. Elevated proteins were noted in about a third of patients while a few patients also demonstrated the presence of antithyroid antibodies in CSF. Mild or nonspecific inflammation characterized by mononuclear pleocytosis or elevated proteins are common in HE and rarely oligoclonal bands have also been reported.[673]

A few limitations of the present review should be kept in mind. We included only published case reports in English language journals. Hence, it is possible that some reports may not have been included. Another shortcoming was that we relied only on data available in the published manuscripts and did not contact authors for more information. As the review focused only on case reports and case series, we did not attempt a quantitative synthesis of data.

CONCLUSION

Psychiatric presentations heralding HE can be quite heterogeneous but mostly comprise of acute psychotic episodes followed by depression. Schizophrenic presentations and frank dementia may occur less commonly. Antithyroid peroxidase may be a more useful and sensitive marker than anti-TG levels. EEG, MRI, and CSF findings are nonspecific and seem to be reversible with treatment. Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion when dealing with psychiatric presentations in individuals above 40 years of age. Subtle clinical clues such as atypical age of onset, poor response to isolated antipsychotic or antidepressant therapy coupled with raised antithyroid antibody titers should point the finger toward HE. Prevalent thyroid status does not seem to be a clinically useful metric. Evidence suggests that steroid dose needs to be initiated at 500–1000 mg/day for first 3–5 days and it may be prudent to continue oral prednisolone (1–2 mg/kg/day) for few weeks to months followed by gradual tapering. Keeping the above considerations in mind can facilitate an early diagnosis and hasten resolution of HE.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Steroid-responsive encephalopathy associated with autoimmune thyroiditis. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:197-202.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto's encephalopathy: A steroid-responsive disorder associated with high anti-thyroid antibody titers – Report of 5 cases. Neurology. 1991;41(Pt 1):228-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto encephalopathy: A rare intricate syndrome. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;10:506-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Encephalopathy associated with autoimmune thyroid disease in patients with Graves' disease: Clinical manifestations, follow-up, and outcomes. BMC Neurol. 2010;10:27.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and diagnostic aspects of encephalopathy associated with autoimmune thyroid disease (or Hashimoto's encephalopathy) Intern Emerg Med. 2006;1:15-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- The human anti-thyroid peroxidase autoantibody repertoire in Graves' and Hashimoto's autoimmune thyroid diseases. Immunogenetics. 2002;54:141-57.

- [Google Scholar]

- Encephalopathy associated with Hashimoto thyroiditis: Pediatric perspective. J Child Neurol. 2006;21:1-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Encephalopathy in compensated Hashimoto thyroiditis: A clinical expression of autoimmune cerebral vasculitis. Brain Dev. 1986;8:60-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Steroid responsive encephalopathy associated with autoimmune thyroiditis presenting with late onset depression. Neurosciences (Riyadh). 2010;15:196-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Unusual presentations of Hashimoto's encephalopathy: Trigeminal neuralgiaform headache, skew deviation, hypomania. Endocrine. 2011;40:495-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute psychiatric presentation of steroid-responsive encephalopathy: The under recognized side of autoimmune thyroiditis. Riv Psichiatr. 2013;48:169-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- The misdiagnosis of steroid-responsive encephalopathy associated with autoimmune thyroiditis as masked depression in an elderly euthyroid woman. Psychosomatics. 2013;54:599-603.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto's encephalopathy: Report of three cases. J Formos Med Assoc. 2014;113:862-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Severe complication of catatonia in a young patient with Hashimoto's encephalopathy comorbid with Cornelia de Lange syndrome. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2015;31:60-1.

- [Google Scholar]

- Presenile dementia: A case of Hashimoto's encephalopathy. East Asian Arch Psychiatry. 2011;21:32-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Steroid responsive encephalopathy associated with autoimmune thyroiditis (SREAT) presenting as major depression. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:184.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto's encephalopathy mimicking presenile dementia. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36:360.e9-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- A case of Hashimoto's encephalopathy presenting with acute psychosis. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2014;26:E1-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Autoimmune schizophrenia? Psychiatric manifestations of Hashimoto's encephalitis. Cureus. 2016;8:e672.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto's encephalopathy: Systematic review of the literature and an additional case. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;23:384-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Manifestation of Hashimoto's encephalopathy with psychotic signs: A case presentation. Dusunen Adam J Psychiatry Neurol Sci. 2016;29:85-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychotic symptoms in a patient with Hashimoto's thyroditis. Br J Med Med Res. 2013;3:262-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Attempted infanticide and suicide inaugurating catatonia associated with Hashimoto's encephalopathy: A case report. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Steroid responsive encephalopathy associated with autoimmune thyroiditis (SREAT) or Hashimoto's encephalopathy: A case and review. Psychosomatics. 2011;52:99-108.

- [Google Scholar]

- A case of Hashimoto's encephalopathy presenting with seizures and psychosis. Korean J Pediatr. 2012;55:111-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute mania in a patient with hypothyroidism resulting from Hashimoto's thyroiditis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35:683.e1-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Manic symptoms associated with Hashimoto's encephalopathy: Response to corticosteroid treatment. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;23:E20-1.

- [Google Scholar]

- Encephalopathy associated with autoimmune thyroid disease (Hashimoto's thyroiditis) presenting as depression: A case report. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2011;33:641.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical manifestations, diagnostic criteria and therapy of Hashimoto's encephalopathy: Report of two cases. J Neurol Sci. 2010;288:194-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Paroxysmal amnesia attacks due to Hashimoto's encephalopathy. Case Rep Med. 2016;2016:1267192.

- [Google Scholar]

- Neuropsychiatric manifestation of Hashimoto's encephalopathy in an adolescent and treatment. Indian J Psychol Med. 2016;38:357-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rapidly progressive dementia with false-positive PCR Tropheryma whipplei in CSF. A case of Hashimoto's encephalopathy. J Neurol Sci. 2015;355:213-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Subacute cognitive deterioration with high serum anti-thyroid peroxidase antibodies: Two cases and a plea for pragmatism. Psychogeriatrics. 2013;13:175-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute polymorphic psychosis as a presenting feature of Hashimoto's encephalopathy. Asian J Psychiatr. 2016;19:19-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- A case of Hashimoto's encephalopathy manifesting as psychosis. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;9:318-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Affective psychosis, Hashimoto's thyroiditis, and brain perfusion abnormalities: Case report. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2007;3:31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Autoimmune thyroiditis and a rapidly progressive dementia: Global hypoperfusion on SPECT scanning suggests a possible mechanism. Neurology. 1997;49:623-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto encephalopathy presenting as schizophrenia-like disorder. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2009;22:197-201.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto's encephalopathy presenting with bipolar affective disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7:292-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto's encephalopathy presenting with psychosis and generalized absence status. J Neurol. 2004;251:1025-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychiatric presentation of Hashimoto's encephalopathy. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:200-1.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reversible dementia with psychosis: Hashimoto's encephalopathy. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;60:761-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Steroid-responsive encephalopathy associated with Hashimoto's thyroiditis in an adolescent with chronic hallucinations and depression: Case report and review. Pediatrics. 2003;112(3 Pt 1):686-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto's encephalopathy presenting as “myxodematous madness”. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;68:102-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto's encephalopathy masquerading as acute psychosis. J Clin Neurosci. 2008;15:1301-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Atypical neuropsychiatric symptoms revealing Hashimoto's encephalopathy. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:1144-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Skewed X chromosome inactivation and female preponderance in autoimmune thyroid disease: An association study and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:E127-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto encephalopathy (autoimmune encephalitis) J Clin Rheumatol. 2004;10:339-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto's encephalopathy: Epidemiology, pathogenesis and management. CNS Drugs. 2007;21:799-811.

- [Google Scholar]

- Autoantibodies to thyroperoxidase (TPOAb) in a large population of euthyroid subjects: Implications for the definition of TPOAb reference intervals. Clin Lab. 2003;49:591-600.

- [Google Scholar]

- Manifestation of Hashimoto's encephalopathy years before onset of thyroid disease. Eur Neurol. 1999;41:79-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thyroid peroxidase autoantibodies in euthyroid subjects. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;19:1-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Encephalopathy associated with autoimmune thyroid disease: A potentially reversible condition. Case Rep Med. 2016;2016:9183979.

- [Google Scholar]

- The pathogenesis of Hashimoto's thyroiditis: Further developments in our understanding. Horm Metab Res. 2015;47:702-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-term treatment of Hashimoto's encephalopathy. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;18:14-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spectrum of Hashimoto's thyroiditis: Clinical, biochemical and cytomorphologic profile. Indian J Med Res. 2014;140:710-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychosis and EEG abnormalities as manifestations of Hashimoto encephalopathy. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2007;20:138-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Encephalopathy associated with Hashimoto thyroiditis: Diagnosis and treatment. J Neurol. 1996;243:585-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- EEG changes in a patient with steroid-responsive encephalopathy associated with antibodies to thyroperoxidase (SREAT, Hashimoto's encephalopathy) J Clin Neurophysiol. 2006;23:371-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- EEG findings in steroid-responsive encephalopathy associated with autoimmune thyroiditis. Clin Neurophysiol. 2003;114:32-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Electroencephalographic findings in Hashimoto's encephalopathy. Neurology. 1995;45:977-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reversible MRI findings in a patient with Hashimoto's encephalopathy. Neurology. 1997;49:246-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- A follow-up 18 F-FDG brain PET study in a case of Hashimoto's encephalopathy causing drug-resistant status epilepticus treated with plasmapheresis. J Neurol. 2014;261:663-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- The neurological disorder associated with thyroid autoimmunity. J Neurol. 2006;253:975-84.

- [Google Scholar]