Translate this page into:

Lennox–Gastaut Syndrome: A Prospective Follow-up Study

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Objectives:

Lennox–Gastaut syndrome is a catastrophic epileptic encephalopathy. In Lennox–Gastaut syndrome, seizures are resistant to pharmacological treatment. In this prospective study, we evaluated the clinical features, neuroimaging, and response to treatment.

Materials and Methods:

Forty-three consecutive newly diagnosed patients of Lennox–Gastaut syndrome were enrolled in the study. Baseline clinical assessment included seizure semiology, seizure frequency, electroencephalography, and neuroimaging. Patients were treated with combinations of preferred antiepileptic drugs (sodium valproate [VPA], clobazam [CLB], levetiracetam [LVT], lamotrigine [LMT], and topiramate [TPM]). Patients were followed for 6 months. The outcome was assessed using modified Barthel index.

Results:

Tonic and generalized tonic-clonic forms were the most common seizures types. Features suggestive of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (37.2%) were most frequent neuroimaging abnormality. Neuroimaging was normal in 32.6% of patients. With a combination valproic acid (VPA), CLB, and LVT, in 81.4% of patients, we were able to achieve >50% reduction in seizure frequency. Eleven (25.58%) patients showed an improvement in the baseline disability status.

Conclusions:

A combination of VPA, CLB, and LVT is an appropriate treatment regimen for patients with Lennox–Gastaut syndrome.

Keywords

Clobazam

Lennox–Gastaut syndrome

levetiracetam

seizure

valproic acid

INTRODUCTION

Lennox–Gastaut syndrome is a form of epileptic encephalopathy characterized by multiple seizure types, generalized slow spike-wave discharges on electroencephalography, and impaired mental functions with or without behavior abnormalities. Seizure types that are frequently encountered include tonic, atypical absence, atonic, generalized tonic-clonic, myoclonic, and focal seizures.

Treatment of Lennox–Gastaut syndrome is always difficult, and the possibility of complete seizure control remains grim. All patients have drug-resistant, lifelong epilepsy. Many drugs such as valproic acid (VPA), clobazam (CLB), topiramate (TPM), levetiracetam (LVT), and lamotrigine (LMT) are considered preferred drugs.[123] The choice of the most effective antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) is difficult and often a combination of antiepileptic drugs are needed. There is little guidance available for the most effective AEDs combination. Physicians need to consider each patient individually, taking into account the benefit and the risk of adverse effects of each combination.

This prospective study was planned to evaluate seizure control in patients with Lennox–Gastaut syndrome. We used the preferred drugs that are commonly used (as monotherapy or in combination) in the treatment of Lennox–Gastaut syndrome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This prospective observational study was conducted in the Department of Neurology of King George's Medical University Uttar Pradesh, Lucknow, India. Study was approved by Institutional Ethical Committee of King George's Medical University. Written informed consent from parents or relatives was obtained before patients were included in the study. Consecutive newly diagnosed patients of Lennox–Gastaut syndrome were included in the study. Patients were enrolled from November 2012 to March 2014. All data were recorded at baseline and at monthly interval till 6 months from baseline on a predesigned pro forma.[4]

The diagnosis of Lennox–Gastaut syndrome was based on the International League Against Epilepsy classification guidelines.[5] The included patients had experienced at least two types of seizures; electroencephalography showed slow spike-wave discharges and/or episodic fast activity and mental retardation. Patients, later diagnosed with a different epileptic syndromes or diseases, were excluded from the study.

After inclusion, a detailed neurological evaluation was done. Seizure types were ascertained on the basis of eyewitness account, observation in the ward, and/or the review of videos recorded by parents. Patient's disability status was assessed by the modified Barthel index. Electroencephalography, neuroimaging (computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging), and a battery of laboratory tests (complete hemogram, plasma glucose, renal function test, liver function test, and electrolytes) were performed in each case at inclusion. We did not perform a detailed workup for metabolic or genetic causes. We did not monitor AED levels.

Tonic seizure was defined as a sustained increase in muscle contraction lasting a few seconds to minutes. Atonic seizures were considered when there was sudden loss or diminution of muscle tone without an apparent preceding myoclonic or tonic event. Tonic-clonic seizures were defined by a sequence consisting of a tonic followed by a clonic phase. Myoclonic seizures were defined as a sudden, brief involuntary single, or multiple contraction(s) of muscle(s) or muscle groups. Atypical absence seizures were considered in patients with severe symptomatic or cryptogenic epilepsies with a slow onset and termination of episodes with an electroencephalography demonstrating showing slow spike-wave discharges.[6]

Patients with Lennox–Gastaut syndrome were started on antiepileptic drugs based on available guidelines and literature.[17] VPA was used as the first-line drug. If the decrease in seizure frequency was <50%, then CLB was added to VPA; if even then the decrease in seizure frequency was <50%, then LVT was added to previous combination. Subsequent additions were planned as LMT, followed by TPM, and then clonazepam. Response to treatment was defined as >50% reduction in seizure frequency relative to pretreatment status.[7] All patients were followed clinically at monthly intervals for their seizure profile and assessment of overall disability with the help of 20-point modified Barthel index. A change of >2 points in the modified Barthel index was considered significant. Parents were advised to maintain a seizure diary.

The statistical analysis was done using Microsoft Excel (version 15.16). Continuous variables were expressed as mean while categorical variables were expressed as percentages.

RESULTS

During the study period, 67 patients of Lennox–Gastaut syndrome were screened. Forty-eight patients were included in the study. Nineteen patients did not meet the inclusion criteria. Five patients were lost to follow-up. Thus, 43 patients were finally available for evaluation and final analysis [Figure 1].

- Flow diagram of the study

Age of patients ranged from 2 to 14 years with a mean of 6.71 years. Tonic and generalized tonic-clonic seizures were the most frequent seizure types seen. Myoclonic seizures were seen in approximately 37% of cases [Table 1].

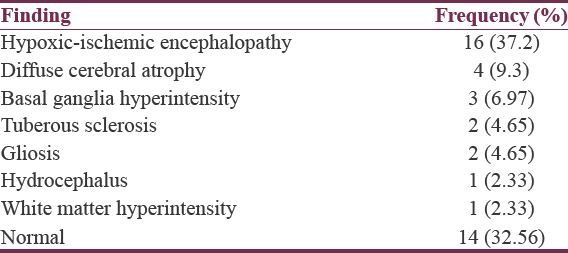

Neuroimaging finding

Neuroimaging abnormalities (hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, diffuse cerebral atrophy, basal ganglia hyperintensity, gliosis and tuberous sclerosis, hydrocephalus, or white matter hyperintensity) were reported in 29 patients (67.44%). In rest (14; 32.56%), neuroimaging was normal [Table 2].

Seizure reduction at 6 months

With usage of VPA, CLB, and LVT, we were able to reduce seizure frequency by 50% in 81.4% of patients. Equal amount of seizure reduction following antiepileptic treatment was observed both in patients with or without neuroimaging abnormalities [Table 3].

Effect of seizure reduction on disability

Only 11 (25.58%) patients showed an improvement in the disability status. Majority (32; 74.42%) of children did not show any significant change in the modified Barthel index.

Side effects of antiepileptic drugs

Five patients experienced transient sedation and/or unsteadiness of gait after addition of CLB. Sedation and/or unsteadiness of gait improved within 7 days. Withdrawal or dose reduction of drug was not needed in any of the patient.

DISCUSSION

We observed that commonly used AEDs (sodium valproate, CLB, LVT, LMT, and TPM) in combination reduce the seizure frequency to 50% in >80% of patients; however, disability scale remains unaltered in the majority.

AEDs are the mainstay in treatment of Lennox–Gastaut syndrome. Unfortunately, no single drug is capable of providing seizure freedom in such patients. Frequent exacerbations in the seizure frequency are common in these patients, and in a large number, seizure control is difficult. The clinicians, thus, have to resort to AED combinations.[7] Our experience suggests that clinician should try most effective drugs that are generally recommended for Lennox–Gastaut syndrome in combination. Other forms of treatment such as corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, ketogenic diet, and vagus nerve stimulation may provide benefit in some patients. Epilepsy surgery should be considered in selected resistant cases.[8]

The cause of Lennox–Gastaut syndrome can be categorized into symptomatic (secondary to a definite brain disorder) and cryptogenic (apparently normal) groups. We observed neuroimaging abnormalities in approximately 67% of patients, and a definite cause could not be identified in the rest one-third. In resource-constrained countries, there is a high incidence of perinatal insults, leading to an intellectual handicap in the child population. The children with perinatal insults are more vulnerable to develop Lennox–Gastaut syndrome. Other common causes include tuberous sclerosis, congenital infections, hereditary metabolic diseases, and brain malformations.[910]

Our study had certain limitations. A longer follow-up period would have provided more information about the course of illness on AEDs. The natural history of the syndrome shows that the frequency and type of seizures often fluctuate with time. Thus, the benefit observed may not solely be due to the AEDs. A larger sample size would have allowed more number of patients in each group with appropriate statistical analysis.

CONCLUSION

Available AEDs, in combination, help in reducing seizure frequency in majority of Indian patients.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Lennox-Gastaut syndrome: A consensus approach on diagnosis, assessment, management, and trial methodology. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:82-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (childhood epileptic encephalopathy) J Clin Neurophysiol. 2003;20:426-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis and management of the epilepsies in adults and children: Summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ. 2012;344:e281.

- [Google Scholar]

- Proposal for revised classification of epilepsies and epileptic syndromes. Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1989;30:389-99.

- [Google Scholar]

- Glossary of descriptive terminology for ictal semiology: Report of the ILAE task force on classification and terminology. Epilepsia. 2001;42:1212-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Introduction: Recommendations regarding management of patients with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Epilepsia. 2014;55(Suppl 4):1-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-term seizure outcome in 74 patients with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome: Effects of incorporating MRI head imaging in defining the cryptogenic subgroup. Epilepsia. 2000;41:395-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Relationship of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome with perinatal event: A cross-sectional study. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2015;10:98-102.

- [Google Scholar]