Translate this page into:

Penetrating spinal cord injury with screwdriver in situ, leading to Brown-Sequard syndrome

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Sir,

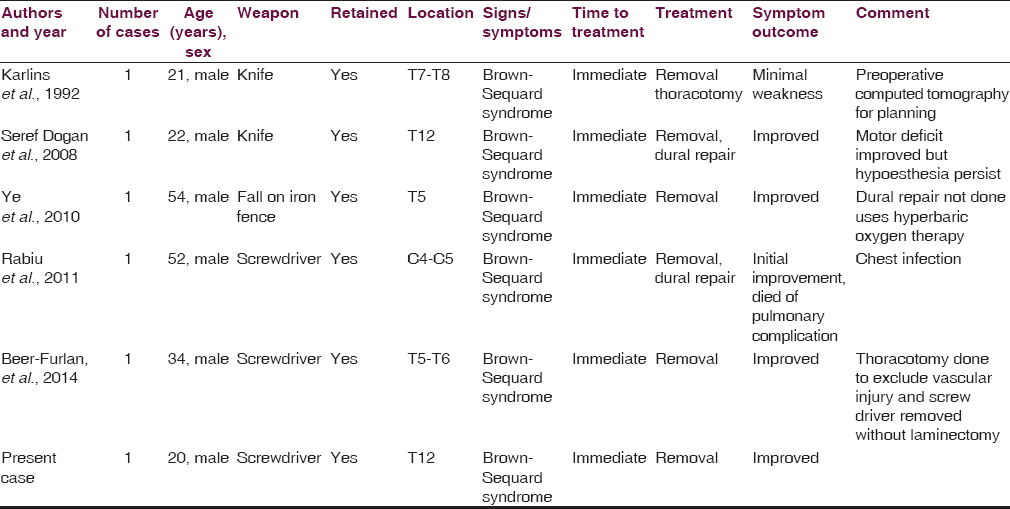

Brown-Sequard syndrome is lateral hemisection of spinal cord characterized by motor weakness and loss of proprioception ipsilateral to the side of the lesion, along with loss temperature and pressure on the contralateral side.[1] It occurs secondary to traumatic, neoplastic, congenital, or degenerative lesions of spinal cord.[1] Penetrating injury constitutes only small number of cases of traumatic origin. Most of the cases of penetrating spinal cord injury are of assaults, industrial, and road traffic accidents. The penetrating object can range from a pencil or chopstick to iron rod, scissors, etc., knife being the most common. Based on nature of the lesion, decompression and/or steroids are used for management of acute cases of Brown-Sequard syndrome.[2] So far only five cases of Brown-Sequard syndrome due to penetrating spinal cord injury with object in situ have been reported [Table 1]. A 20-year-old male was admitted in our institute after being stabbed in the back. On admission, the patient was hemodynamically stable with weakness of the right lower limb. His physical examination revealed small stab wound with retained metallic foreign body in mid-back about 1 cm from the midline on the left side [Figure 1]. Neurological examination of the patient revealed right lower limb paresis with muscle strength of 1/5 at the hip, knee, and ankle joints. There was loss of pain, temperature, and touch sensations below L2 on the left side. Radiograph of thoracic spine shows metallic foreign body at D12 level [Figure 2]. Computed tomography (CT) spine shows long metallic foreign body piercing the skin, subcutaneous tissue on the left side, and traversing the spinal canal from left to right with its tip reaching about mid of vertebral body at D12 level. No spinal angiography could be done in the middle of night. An emergency surgical decompression of the cord was planned. The anesthesiologist could put the endotracheal tube in lateral position. The stab wound extended upward and downward over the midline and D11, D12, and L1 laminectomy was done, which revealed that the screwdriver had penetrated the dura and entered the spinal cord [Figure 3]. Until this point, every attempt was made to avoid even slightest movement of the metallic object relative to the spine. Screwdriver was removed through the same trajectory of its entry after opening the dura above and below in midline. Bleeding from the track was stopped by packing the vertebral body with oxidized cellulose. Dura closed primarily after securing hemostasis. No attempt was made to close the ventral dural defect with suture/glue or dural patch. Postoperative period was uneventful. There was no cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak, patient gradually improved to 4/5 power at hip, knee, and ankle although sensory deficit in the form of hypoesthesia persisted till the last follow-up (3 months back).

- Retained screwdriver in patient back

- Radiograph showing metallic foreign body at D12 level reaching almost up to the mid of vertebral body

- Intraoperative image showing metallic object (screwdriver) penetrated through the spinal cord

In 1849, Charles Edouard Brown-Sequard defined Brown-Sequard syndrome as spinal cord hemisection. It is characterized by ipsilateral motor weakness and loss of proprioception with contralateral loss of pain and temperature sensations. Most patients affected are between 15 and 50 years of age. Thoracic spine is most commonly involved followed by cervical and lumbar spine with frequency of 75%, 17%, and 8%, respectively.[2] Etiologically, Brown-Sequard syndrome is classified into two broad categories: Traumatic and nontraumatic. Nontraumatic causes include arachnoid cyst, syringomyelia, hematomyelia, and herniated disc. Traumatic causes are more common and include penetrating injury, gunshot injury, and blunt injuries.[1] Although stab injuries of spinal cord are rare entities, its incidence varies widely in different parts of the globe. While there have been few reports from India,[3] reports from South Africa account for majority of large series.[456] The majority of these injuries are due to assault with knife stabbing. Penetrating injury can occur due to fall on a pointed object, stabbing with scissors, garden fork, and sickles, etc., Screwdrivers are infrequently used in assaults leading to spinal cord injuries.[78] As a weapon, it can apply a concentrated force to a small area, with rigid stream allowing it to penetrate bone more easily as compared to a blade. In most circumstances, weapon is withdrawn after attack by assailant but some time weapon remains impacted in bone and retained either as whole or as fragments as in our case. These patients pose a challenge in terms of transportation, positioning, and management. There are no well-established guidelines for managements of these patients. The optimal management consists of careful transportation to a hospital and basic trauma care. A complete assessment should be done to rule out injuries to major vascular structures and visceral organs. Manipulation or removal of retained foreign body in these patients before imaging and neurosurgical consultation should be avoided as it may lead to increase the risk of bleeding, neurological damage, and infection.[9]

After appropriate initial trauma assessment and resuscitation, radiological studies should be done for the evaluation of penetrating spinal cord injuries. Most authors recommend plain X-ray and CT scan to know the presence of retained foreign body, level of lesion, vertebral fracture, and relation between foreign body and spinal cord.[9] Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging is contraindicated in cases where metallic foreign body is suspected as it can worsen the neurological deficit due to movement of foreign body by strong magnetic field.[9]

The surgical management of penetrating spinal injuries is controversial, and no definite management guidelines exist. The consensus is that surgical exploration should be done in patients with incomplete neurological deficits, persistent CSF leak, retained intraspinal foreign body or bone fragments, and persistent pain.[9] In patients with retained foreign material, exploration should be done in the acute phase of injury as foreign material can lead to both acute and chronic neurological and infectious consequences.[9] Surgical procedure involves laminectomy, defining the normal dura cranial and caudal to the site of stab, and opening the dura with stay sutures. Conservative debridement is carried out, and only the detached, nonviable neural tissue is debrided. A hematoma is evacuated and dura is closed, with a dural substitute if necessary. Lumbar subarachnoid CSF drain is inserted for 5–10 days and antibiotics in antimeningitic dosage are administered.[10]

Although late complications such as myelopathy, intramedullary abscess, progressive neurological deficit, and symptomatic pseudomeningocele have been reported due to foreign material, no spinal instability has been reported. Prognosis for the stab injuries is better than the gunshot wound with recovery being reported in more than 66% of incomplete injuries.[11]

Penetrating injury of the spinal cord with retained metallic object is a rare entity and may be even “once in a lifetime” experience in the life of even reasonably experienced neurosurgeons practicing in the civil (nonmilitary) settings. One has to be very cautious in transporting, investigating, and intubating such patients in the lateral position, etc., An early surgical intervention wherever indicated is the key to good outcome in these patients.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Spinal cord injury. Role of steroid therapy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1994;19:2281-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spinal epidural haematoma: Report of 11 cases and review of the literature. Neuroradiology. 1994;36:456-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Non-missile penetrating injuries of the spine. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1991;113:144-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Associated injuries and complications of stab wounds of the spinal cord. Paraplegia. 1967;5:75-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Penetrating spinal injury inflicted by screwdriver: Unusual morphological findings. J Clin Forensic Med. 1995;2:153-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nonmissile penetrating spinal injury. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg Spine. 2006;4:400-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Changing profiles in spinal cord injuries and risk factors influencing recovery after penetrating injuries. J Trauma. 1995;38:334-7.

- [Google Scholar]