Translate this page into:

Headache in the presentation of noncephalic acute illness

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Headache is a frequent symptom of many systemic diseases that do not involve cranial structures. In this observational study, we assessed factors associated with headache in the acute presentation of systemic conditions in a nonsurgical emergency department (ED).

Methods:

Consecutive patients, admitted to Soroka University Medical Center ED due to noncephalic illness, were prospectively surveyed using a structured questionnaire focused on the prevalence and characteristics of headache symptoms. Medical data were extracted from the patient's charts.

Results:

Between 1 and 6/2012, 194 patients aged 64.69 ± 19.52 years, were evaluated. Headache was reported by 83 (42.7%) patients and was more common among patients with febrile illness (77.5% vs. 22.5%, P < 0.001). Respiratory illness and level of O2 saturation were not associated with headache. Headache in the presentation of a noncephalic illness was associated with younger age (58 vs. 69, P < 0.001) and with suffering from a primary headache disorder (48.2% vs. 10.8%, P < 0.001). Headache was also associated with higher body temperature and lower platelets count.

Conclusions:

Headache is a common symptom in acute noncephalic conditions and was found to be associated with younger age and febrile disease on presentation. Patients who present with primary headache disorders are more prone to have headache during acute illness. Acute obstructive respiratory disease, hypercarbia or hypoxemia were not associated with headache.

Keywords

Emergency department

fever

headache

migraine

Introduction

Headache is a common symptom of many diseases; it directly involve intracranial or cephalic pathologies such as sinusitis or otitis media.[1] Headache may present as the hallmark of the disease in other systemic conditions such as hypertensive crisis,[2] preeclampsia,[3] or Rickettsia infections.[4]

However, headache is a common symptom in many common acute noncephalic conditions as well. Previous studies showed an association between acute headache and various febrile conditions such as pneumonia, upper respiratory tract infection (URTI),[567] systemic viral infections (especially caused by human metapneumovirus respiratory tract infection),[8] and even urinary tract infections (UTI).[9] Other noninfectious conditions such as: Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or asthma, anemia, congestive heart failure (CHF),[1011] fasting,[12] and elevated blood pressure (without hypertensive crisis) were all associated with headache as well.[13]

Many clinical factors were found to be associated with acute headache during illness. Fever is usually considered to be the most important determinant,[8] but other factors such as hypoxia and hypercapnia not only due to pulmonary disease[14] but also due to obstructive sleep apnea and high altitude,[15] hypoglycemia,[16] hypothyroidism,[17] and dehydration[18] were all found to be independently associated with acute headache.

In this study, we sought to evaluate the characteristics associated with an acute headache among patients with noncephalic acute medical condition.

Methods

Setting

Emergency department (ED) of Soroka University Medical Center (SUMC), a tertiary referral, 1000 beds medical center, and serving over 700,000 residents of Southern Israel. The 60 beds ED treats over 500 adult patients a day on average. This prospective observational study took place at the medical ED. The study was approved by the SUMC internal review board.

Patients

The acutely adult ill medical patients were screened between January and June 2012. Patients presenting with chief complaint of headache, acute cephalic illness (stroke, seizures, cranial lesions, sinusitis, or central nervous system infections), treated with vasodilators for hypertensive crisis or chest discomfort, or those with chronic headache (>14 days of headache per month for longer than 3 months) were excluded. Patients younger than 18 and who could not give an adequate headache history due to either the severity of their medical condition, language barrier, or cognitive impairment were excluded as well.

Data collection

Patients were interviewed using a structured questionnaire by a surveyor who was not involved in the patients’ medical care. The questionnaire was designed to capture headache symptoms, headache history, as well as demographic data. The following clinical data were extracted from the patients’ ED chart: Vital signs, O2 saturation, primary diagnosis, diagnostic procedures, and blood test results.

Patients were asked to report if they had to deal with headache attacks that are not related to acute medical illness during the last year (active episodic headache) and whether they used to have headache during similar medical events in the past (at least once).

Statistical analysis

The preferred method of analyses for continuous variables was parametric. Nonparametric procedures were used only if parametric assumptions could not be satisfied, even after data transformation attempts. Parametric model assumptions were assessed using normal plot or Shapiro–Wilk's statistic for verification of normality and Levene's test for verification of homogeneity of variances. Categorical variables were tested using Pearson's Chi-square test for contingency tables or Fisher exact test, as appropriate. Multivariate analysis was performed by Poisson regression with robust error variance.[19] Modified Poisson approach was used to estimate the relative risk (RR) adjusted for potential confounders. Variables were included into the model based on the statistical and clinical significance. We reported the final parsimonious model.

To evaluate the possible nonlinear association between the body temperature and probability of the headache, we have used headache predicted probabilities by local regression (LOESS) curves adjusted for: Gender age, platelet count, saturation level, and similar problem before.

Results are presented as RRs with confidence intervals, mean (±standard deviation), and median (interquartile range).

Two-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. IBM SPSS statistics 20.0 software (IBM) was used for the statistical analysis results.

Results

During the study, 199 patients were recruited. Five patients were not included in the final analysis due to incompleteness of the clinical data. The distribution of the primary diagnosis was as following: CHF (37, 19.0%), COPD exacerbation (34, 17.5%), pneumonia (15, 7.7%), URTI (23, 11.9%), exacerbations of asthma (21, 10.8%), UTI (18, 9.3%), hypertension (15, 7.7%), and fever of undetermined cause (31, 16.0%). Out of the 194 evaluated patients, 52 (26.8%) patients had unprovoked episodes of headache.

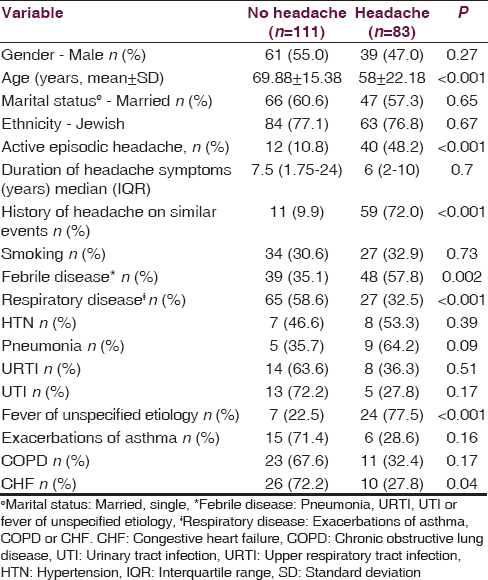

Headache was reported during the current acute illness by 83 (42.8%) of the patients. The headache was of moderate (35, 42.0%) to severe (30, 36.0%) intensity, bilateral (68, 76.0%) or localized to the frontal regions of the head (45, 54.2%), and generalized in 20 patients (24.1%). Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of patients with and without headache. Patients with headache were younger (median age 69.88 ± 15.38 vs. 58 ± 22.18, P < 0.001) and had higher proportion of active primary headache: 40 (48.2%) versus 12 (10.8%), P < 0.001. Patients with febrile illness had significantly higher rate of headache: (48, 57.8%) versus 39 (35.1%), P < 0.001.

Table 2 depicts the clinical parameters of the acute illness. The presence of headache was positively associated with body temperature, pulse rate, hemoglobin, and O2 saturation and negatively associated with concentrations of creatinine, urea and potassium, and platelet count. Hospitalization duration did not differ between those with and without headache: 5 (3–8) days versus 4.5 (2.75–6), P = 0.21.

Multivariate analysis [Table 3] found that younger age (P = 0.007, RR = 0.98), higher body temperature (P = 0.017 RR = 1.21), experiencing headache on similar conditions (P < 0.001, RR = 3.89), and lower platelet count (P < 0.001, RR = 0.96) were independently associated with headache. Gender, oxygen saturation, urea to creatinine ratio, and blood urea levels were not associated with headache. Figure 1 (LOESS analysis) confirms the independent association between headache and body temperature. After adjustment for gender, age, platelet count, saturation level, and similar previous headache, we have found that higher the fever is, higher the chances to have a headache.

- Association between headache and body temperature. Local regression (LOESS) curves, based on the probabilities of headaches, adjusted for: Body temperature, gender, age, platelet count, saturation level and similar headache before

Discussion

We found that headache is an extremely common symptom experienced by more than 40.0% of the patients evaluated in the medical ED due to acute noncephalic illness, most of them experiencing moderate to severe pain, adding to the discomfort from the acute illness. Our results demonstrate that the likelihood of headache is associated with younger patient's age, a history of headache on similar circumstances, elevated body temperature, and lower platelet count.

Other patient characteristics (such as gender, ethnicity, and smoking) were not associated with headache during acute illness. Several clinical parameters in univariate analysis were found to be significantly associated with headache: Higher levels of hemoglobin, creatinine, urea and potassium as well as lower O2 saturation. Nevertheless, the association lacked clinical relevance and did not reach statistical significance in multivariate analysis.

Headache disorders are chronic disorders with episodic manifestations. Active headache disorders are characterized by the occurrence of headache episodes within the previous year.[20] Active headaches are reported by 53.0% of adult population and active migraine by 14.7% of the population.[21] In our cohort, the prevalence of active headache was relatively low (26.8%) possibly due to the relatively old age of the study population.

An active headache disorder probably represents personal vulnerability to headache, possibly triggered by the acute illness. Most of the patients experiencing headache in our cohort, reported experiencing headache in similar occasions in the past.

As was suggested previously, fever is part of a systemic presentation considered to be a trigger for headache.[8] A cross-sectional epidemiologic survey of a representative 25–64-year-old general population demonstrated that lifetime prevalence of fever- induced headaches was 63.0%.[22] Furthermore, among children aged 0–14, suspected infections and fever accounted for 56.8% of the headache and migraine episodes.[23] Our study confirms the close independent association between headaches and fever.

Several pathophysiological mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of primary headaches may be affected by fever. Pyrogenic cytokines (interleukin-1 [IL-1], IL6) and prostaglandins cause rise in temperature.[24] Body temperature is largely regulated by the hypothalamus and the induction of fever is believed to be caused by inflammatory modulation of its activity.[25] The hypothalamus is also involved in the pathophysiology of migraine mediated by calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP).[262728]

Recently, the role of CGRP in migraine pathophysiology was extensively studied. CGRP seems to be involved in the evolution of bacteria-induced hyperpyrexia. It has been suggested that bacteria activate CGRP through lipopolysaccharide and endotoxins. This activation leads to secretion of IL1 and IL6, which in turn, activate the hypothalamus and cause fever.[29] Inflammatory mediators themselves are contributors to the pathophysiology of both tension-type and migraine headache, and anti-inflammatory drugs are commonly used as acute treatments for headache attacks.[30]

Activation of the serotonergic system, especially through 5HT1 receptors is considered as a major part of migraine pathophysiology.[31] Serotonergic system activation is involved in hyperpyretic states as demonstrated by hyperthermia during episodes of serotonergic syndrome,[32] and by the temperature lowering effect of 5HT1A agonist on patients infected by Plasmodium falciparum.[33] It has been speculated that migraine attacks are caused by dysregulation of brain temperature, possibly as a defense mechanism.[34]

The association between lower platelet count and headache during acute medical illness is small, yet significant and independent. Several lines of evidence suggest that increased platelet activity is associated with migraine attacks.[35] Furthermore, as explained before increased levels of 5HT during migraine causes reversible platelets aggregation.[36] Thus, the suggested mechanism explains that increased platelet aggregation, slightly decreasing the platelet count, possibly lead to the association between lower platelet count and headache in an acute illness. It was also suggested that sub-clinical platelet aggregation may induce headache attacks.

Our study has several limitations. It is a single-center study, with a relatively small sample size, limited to patients referred to the ED, therefore its generalizability to other clinical settings is limited. By excluding cephalic illnesses, we could not evaluate the diagnostic contribution of headache in differentiating cephalic from noncephalic disorders. Patients who were actively complaining about headache where not all diagnosed as suffering from migraine or tension-type headache.

Nevertheless, it seems that headache is a common distressing contributor in acute ED patients. It seems that alleviation of headaches in those settings should be directed to temperature lowering. Larger studies are needed to evaluate the significance of the association between headache and lower platelet count in acute medical illness conditions.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

This work was performed in partial fulfillment of the M.D. thesis requirements of the Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev.

References

- Prevalence of nasal mucosal contact points in patients with facial pain compared with patients without facial pain. J Laryngol Otol. 2001;115:629-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hypertensive urgencies and emergencies. Prevalence and clinical presentation. Hypertension. 1996;27:144-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Migraine headaches and preeclampsia: An epidemiologic review. Headache. 2006;46:794-803.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rickettsial infections and fever, Vientiane, Laos. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:256-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- A practical approach to adult acute respiratory distress syndrome. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2010;14:196-201.

- [Google Scholar]

- Is headache related to asthma, hay fever, and chronic bronchitis?. The Head-HUNT study. Headache. 2007;47:204-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical picture of community-acquired Chlamydia pneumoniae pneumonia requiring hospital treatment: A comparison between chlamydial and pneumococcal pneumonia. Thorax. 1996;51:185-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characteristics of human metapneumovirus respiratory tract infection in children and the relationship between the infection and meteorological conditions. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2011;49:214-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and laboratory characteristics of acute community-acquired urinary tract infections in adult hospitalised patients. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2010;10:49-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Migraine and risk of cardiovascular disease in men. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:795-801.

- [Google Scholar]

- Water-deprivation headache: A new headache with two variants. Headache. 2004;44:79-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- Blood pressure and risk of headache: A prospective study of 22 685 adults in Norway. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;72:463-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Are morning headaches part of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome? Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:1265-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endocrine headache. In: Seminars in headache management. Neuroendocrinological aspects of headache. Vol 4. Canada: B.C. Decker Inc; 1999. p. :1-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:702-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The international classification of headache disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(Suppl 1):9-160.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of headache in Europe: A review for the Eurolight project. J Headache Pain. 2010;11:289-99.

- [Google Scholar]

- Symptomatic and nonsymptomatic headaches in a general population. Neurology. 1992;42:1225-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Immunological and inflammatory functions of the interleukin-1 family. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:519-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kinetics of systemic and intrahypothalamic IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor during endotoxin fever in guinea pigs. Am J Physiol. 1993;265(3 Pt 2):R653-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Vasoactive peptide release in the extracerebral circulation of humans during migraine headache. Ann Neurol. 1990;28:183-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intrinsic brain activity triggers trigeminal meningeal afferents in a migraine model. Nat Med. 2002;8:136-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Involvement of cytokines in lipopolysaccharide-induced facilitation of CGRP release from capsaicin-sensitive nerves in the trachea: Studies with interleukin-1beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. J Neurosci. 1996;16:4742-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Practice parameter: Evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache (an evidence-based review) Neurology. 2000;55:754-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Modulation of the activity of midbrain central gray substance neurons by calcium channel agonists and antagonists in vitro. Neuroscience. 1996;70:159-67.

- [Google Scholar]

- 5HT1A serotonin receptor agonists inhibit Plasmodium falciparum by blocking a membrane channel. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:3806-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Alterations in brain temperatures as a possible cause of migraine headache. Med Hypotheses. 2014;82:529-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Migraine: Possible role of shear-induced platelet aggregation with serotonin release. Headache. 2012;52:1298-318.

- [Google Scholar]