Translate this page into:

Clinical spectrum and radiographic features of the syndrome of the trephined

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Object:

Craniectomy is a common neurosurgical procedure. Syndrome of the trephined (ST) occurring after craniectomy results in neurologic symptoms that are reversible with cranioplasty. While well-documented, previous literature consisted of case reports, symptom spectrum and risk factors have not been well characterized.

Materials and Methods:

A retrospective review of 29 consecutive cases who underwent decompressive craniectomy within a 30-month period was performed. Patients were considered affected by ST if a previously stable neurological deficit improved within 3 weeks after cranioplasty. Prevalence of ST was measured and association with demographic information, clinical symptoms patterns, indication for and size of craniectomy, as well as radiological signs were tested.

Results:

Seven patients (24%) developed ST. Chronic rehabilitation arrest was more common than acute neurologic decline. Factors such as craniectomy size and patient age did not reach statistical significance in development of ST. Radiographic factors were predictive, with a sunken skin flap contour being most sensitive, while ventricular effacement was most specific.

Conclusion:

ST may have a higher incidence than previously thought, with a chronic rehabilitation arrest being a more common presentation than an acute decline. Medical providers involved in the post surgical care and rehabilitation of these patients should maintain a high index of suspicion for ST.

Keywords

Craniectomy

trephined

trauma

rehabilitation

Introduction

Craniectomy is an increasingly common neurosurgical procedure for a variety of pathologic processes. The syndrome of the trephined (ST) results in reversible neurologic symptoms or behavioral disturbance and has been described after craniectomy. The term was originally coined by Grant in 1939 and was thought to be largely psychiatric in nature, attributed to a “sense of vulnerability” from the lack of an intact cranial vault.[1] The syndrome has also been called the “syndrome of the sinking skin flap” by Yamaura and Makino.[2] The spectrum of symptoms resulting from this syndrome can range from seizures, headache, neurospsychiatric disturbance, focal weakness, midbrain syndromes,[3] and Parkinsonian symptoms.[4] Initial series of patients with this syndrome were small, to which a variety of case reports have been added since its first description. The significance of this syndrome has increased in recent years due to the increasing popularity of large craniectomies for such pathology as trauma and malignant infarction. It remains poorly characterized in terms of risk factors, incidence, diagnosis, and clinical spectrum. This study aims to report the prevalence, clinical characteristics, and radiological signs associated with the syndrome of the trephined.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective analysis was performed after IRB approval, with the aim to assess the clinical spectrum and radiographic features of ST. All patients undergoing craniectomy for any reason followed by cranioplasty within a 30-month period were included for analysis based on review of our facility's operative procedures database, and a case-control analysis was conducted comparing those with and without ST, as defined by clinical criteria of a neurologic deficit which improved within 3 weeks of cranioplasty. Patients undergoing craniectomy without cranioplasty were excluded.

The symptom complex, reason for craniectomy, craniectomy size, demographic data, and radiographic findings were noted. Both clinical follow-up data and radiographic studies were reviewed. Radiographic findings were gleaned from both pre and postoperative computed tomography (CT) imaging. The craniectomy size was defined as the maximal anteroposterior diameter as visualized on CT, based on previous work by our group.[5] Radiographic findings noted included ventricular effacement, midline shift, and a sunken scalp flap contour as seen on CT. These findings were evaluated for their sensitivity and specificity in patients with ST. Ventricular effacement refers to that of the ipsilateral ventricle toward the midline. Midline shift was measured in the standard fashion at the level of the Foramen of Monroe. A sunken scalp flap contour was noted if the scalp flap margin was located below the level of the cranium.

Statistical analysis included comparison of the two groups using P values, with statistical significance being defined as a P value of less than 0.05. Between-group comparisons using discrete numerical data were analyzed using Fisher's exact test (with a Freeman-Halton extension for the analysis of a 2 × 4 contingency table). Between-group comparisons using continuous numerical data were analyzed using unpaired T-tests.

Results

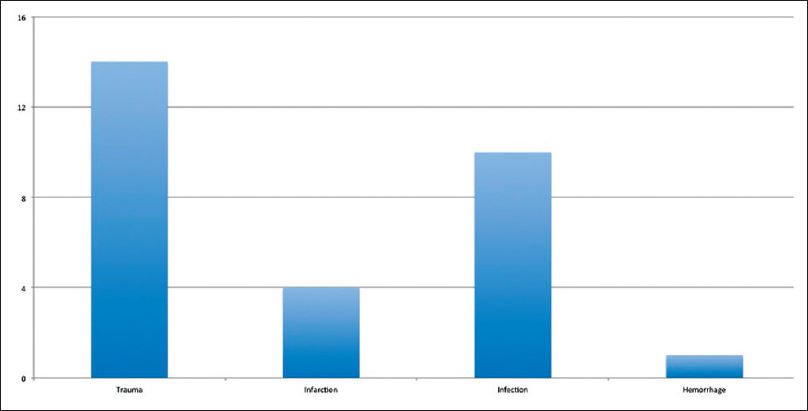

The entire patient cohort consisted of 29 patients. The average age was 34.7 years. The underlying reason for craniectomy consisted of trauma, infarction, infection, and hemorrhage, although the most common pathology was trauma [Figure 1]. The average craniectomy size for the entire cohort was 9.6 cm. All were lateral craniectomies. Two patients were lost to follow up. In the entire cohort, 7 patients developed ST (24% of the total cohort; 25.9% of the patients for which follow up was available).

- Bar graph demonstrating the distribution of etiologies for craniectomy

In those patients developing ST, the syndrome presented either as a chronic arrest of rehabilitation (five patients) or as acute deterioration (two patients). The presenting symptoms included tremor, paresis, aphasia, and behavioral/cognitive deficits. ST did not occur in any patients undergoing craniectomy for infection, which may relate to a smaller overall craniectomy size (average 8.1 cm). Headache was not a presenting symptom for any patient. Time between craniectomy and cranioplasty varied from 4 weeks to up to 1 year, depending upon patient condition and comorbidities.

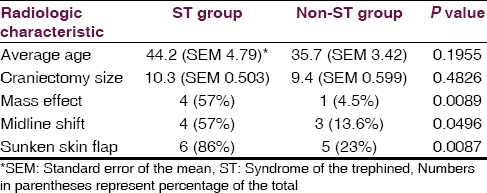

There was no statistically significant difference in patient age or craniectomy size between ST and non-ST groups, although there was a non-statistically significant trend toward ST development in older patients and those with larger craniectomies [Table 1]. An association between sunken skin flap, midline shift, and ventricular effacement and ST was observed [Table 1]. Skin flap sinking is the most sensitive and ventricular effacement the most specific predictor with 86% and 95%, respectively [Table 2]. Both of the acutely deteriorated patients demonstrated all three radiographic indicators (2/2), while only one of the five chronic ST patients demonstrated all three radiographic indicators.

Illustrative case

A 45-year-old male suffered a malignant, left hemispheric infarction. Because of his young age, and at the strong request of his wife, who noted that he would wish to be alive even if hemiparetic and aphasic as long as he was able to enjoy watching his horses in his yard, a partial temporal lobectomy as well as decompressive craniectomy was performed for brain swelling and decreased consciousness. Post-operatively he experienced a prolonged hospital course complicated by a post-operative wound infection requiring multiple wound washouts. He was able to be discharged to rehab alert and participatory, but hemiparetic on the right with complete expressive aphasia as expected from his stroke. He did well with rehabilitation but due to medical issues and the requirement for clearance from infectious disease prior to his cranioplasty, did not present for cranioplasty until 12 months after his craniectomy. At that time he was ambulatory with a cane, although spastic on the right side, and continued to have expressive aphasia. CT scan demonstrated only a sunken skin flap contour, but other radiographic signs were absent [Figure 2]. The patient underwent placement of a customized cranial implant without complication and was able to be discharged the next day. The patient's wife noted immediate improvement in his ability to verbalize after surgery, and upon his 2 week follow up he was noted to be fluent and conversant, although he has remained spastic and has been unable to return to work.

- Axial, non-contrasted computed tomography of the head demonstrating preoperative (left) and post-operative (right) imaging after cranioplasty in a patient with plateau of speech rehabilitation

Discussion

ST is likely to have an increasing prominence with the growing popularity of decompressive craniectomy for a variety of pathologic entities. A variety of mechanisms have been proposed for ST. The original pathology was thought to be compression of the underlying cortex by infolded scalp skin. Fodstad, et al. implicated CSF hydrodynamic abnormalities including resting pressure, sagittal sinus pressure, buffer volume, elastance at resting pressure, and pulse variations at resting pressure.[6] Changes in oscillatory CSF flow at the craniovertebral junction were demonstrated on dynamic phase-contrast MRI by Dujovny, et al.[7] Stiver, et al. and Sakamoto, et al. found improved cerebral blood flow in a total of three total patients with ST after cranioplasty.[89] We saw no patients with a craniectomy for infection develop ST; however, our finding may be confounded by the smaller craniectomy size in this group.

In our series, the incidence of ST for all patients in the group undergoing craniectomy is 24%. This is a greater incidence than the commonly reported rates of ST for patients undergoing decompressive craniectomy for trauma and may indicate underdiagnosis. In the retrospective series 164 patients undergoing DC, Honeybul and Ho report an incidence of only 1.2%.[10] However, in a later article they document an overall improvement in functional independence measure after cranioplasty in patients with craniectomy, noting that the syndrome of the trephined may be more common than previously thought.[11] Additionally, a retrospective review of 38 patients after decompressive craniectomy for trauma revealed a significantly larger percentage of ST, with 26% of patients developing a “motor trephine syndrome” consisting of monoparesis.[12] This discrepancy may relate to timing of the cranioplasty procedure.

Our combination of etiologies makes determination of exact incidence by etiology difficult, however the etiology of craniectomy was significantly related to the development of ST, with no patients undergoing craniectomy for infection going on to develop this syndrome; however, this may be confounded by a smaller craniectomy size in patients with post op infections. Although in the recent literature, ST is mentioned most frequently in relation to trauma, patients with non-traumatic hemorrhage and malignant infarction also developed ST in our series.

ST may manifest as either chronic arrest of rehabilitation or as acute deterioration and therefore physicians involved in the post-surgical care of these patients as well as rehabilitation should have a high index of suspicion for the development of this syndrome. The presentation of chronic arrest of rehabilitation has previously been described in a series of two cases by Janzen and colleagues.[12] Acute deterioration has been described in cases by Bijlenga and Gottlob, where a sudden change in neurological status occurred in a patient with previously normal functioning, which improved with cranioplasty.[34] Both presentations were seen in our series; however, chronic arrest of rehabilitation was more common and more difficult to diagnose.

We found that there was a non-statistically significant trend toward the development of ST with a larger craniectomy. There is furthermore a non-significant trend toward the development of ST in older patients. It is possible that these factors would become statistically significant in a larger series of patients.

Ventricular effacement, midline shift, and sunken scalp flap contour were all significantly more common in the ST group. Mass effect was most specific for ST while sunken scalp flap contour was most sensitive. These predictive factors may aid in diagnosis of ST and also in counseling of patients and family as to expectations of improvement after cranioplasty, or in timing of the cranioplasty procedure. Importantly, all of these findings were also seen in patients without ST, making the diagnosis a primarily clinical one rather than radiographic. De Araujo and colleagues have recently reported on the importance of an asymmetric optic nerve sheath diameter as a possible predictive factor for neurologic improvement following cranioplasty although that was not explored in our study.[13]

We acknowledge the limitations of this small, retrospective series of patients. However, there is a paucity of literature describing ST and we attempt to add to that knowledge. The collection of prospective, multi-center data would improve our collective knowledge of ST. Additionally, the exploration of pre-operative CT findings and their relation to later development of ST may be useful for further study.

Conclusion

ST may be more common than previously thought. Patient age and craniectomy size did not reach statistical significance. Radiologic factors may be important clues for the diagnosis of ST, with a sunken skin flap contour being most sensitive and mass effect being most specific. Medical providers involved in the post-surgical care and rehabilitation of these patients should maintain a high index of suspicion for ST.

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- Neurological deficits in the presence of the sinking skin flap following decompressive craniectomy. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1977;17:43-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Midbrain syndrome with eye movement disorder: Dramatic improvement after craniplasty. Strabismus. 2002;10:271-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Orthostatic mesodiencephalic dysfunction after decompressive craniectomy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:430-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effect of craniectomy size on mortality, outcome, and complications after decompressive craniectomy at a rural trauma center. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2014;5:212-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of cranioplasty on cerebrospinal fluid hydrodynamics in patients with the syndrome of the trephined. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1984;70:21-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Post-cranioplasty cerebrospinal fluid hydrodynamic changes: Magnetic resonance imaging quantitative analysis. Neurol Res. 1997;19:311-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- CT perfusion imaging in the syndrome of the sinking skin flap before and after cranioplasty. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2006;108:583-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reversible monoparesis following decompressive hemicraniectomy for traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg. 2008;109:245-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-term complications of decompressive craniectomy for head injury. J Neurotrauma. 2011;28:929-35.

- [Google Scholar]

- The impact of cranioplasty on neurological function. Br J Neurosurg. 2013;27:636-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Syndrome of the trephined following bifrontal decompressive craniectomy: Implications for rehabilitation. Brain Inj. 2012;26:101-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Asymmetric optic nerve sheath diameter as an outcome factor following cranioplasty in patients harboring the ‘syndrome of the trephined’. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2013;71:963-6.

- [Google Scholar]