Translate this page into:

Level of literacy and dementia: A secondary post-hoc analysis from North-West India

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Introduction:

A relation between literacy and dementia has been studied in past and an association has been documented. This is in spite of some studies pointing to the contrary. The current study was aimed at investigating the influence of level of literacy on dementia in a sample stratified by geography (Migrant, Urban, Rural and Tribal areas of sub-Himalayan state of Himachal Pradesh, India).

Materials and Methods:

The study was based on post-hoc analysis of data obtained from a study conducted on elderly population (60 years and above) from selected geographical areas (Migrant, Urban, Rural and Tribal) of Himachal Pradesh state in North-west India.

Results:

Analysis of variance revealed an effect of education on cognitive scores [F = 2.823, P =0.01], however, post-hoc Tukey's HSD test did not reveal any significant pairwise comparisons.

Discussion:

The possibility that education effects dementia needs further evaluation, more so in Indian context.

Keywords

Dementia

literacy

North-West India

post-hoc

Introduction

A relation between literacy and dementia has been studied in past and an association has been documented.[1234] However till now investigations of the influence of literacy on dementia have primarily focused on African Americans. The current study was aimed at investigating the influence of level of literacy on dementia in a sample stratified by geography (Migrant, Urban, Rural and Tribal areas of sub-Himalayan state of Himachal Pradesh, India). This study extends our previous works[567] in Himachal Pradesh by examining the influence of literacy, post-hoc, on dementia. The study was based on the hypothesis that level of literacy does not influence dementia. The reason for this hypothesis lay in the understanding that if lack of literacy was a risk factor for dementia, then one would expect to find higher prevalence rates of dementia in societies with lower educational levels, perhaps in pandemic proportions in subgroups with no formal education.

Materials and Methods

Data for the present study was obtained from a study conducted on elderly population (60 years and above) from selected geographical areas (Migrant, Urban, Rural and Tribal) of Himachal Pradesh state in North-west India. A brief description of the source study is given here.

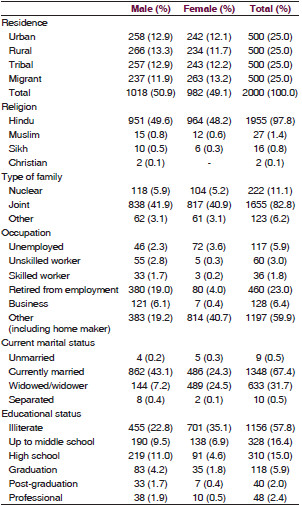

A total of 500 individuals above 60 years of age were included from each geographical site giving us a target sample size of 2000. The study was a cross-sectional study conducted in two phases: (1) A screening phase and (2) a clinical phase. The screening also involved a detail of the socio-demographic profile of study population.

Screening

All subjects were screened, and a subset identified for the detailed clinical evaluation after screening. Trained interviewers administered a standardized Hindi cognitive screening battery, used in a previous study on largely illiterate elderly population in India.[1] This Hindi version of cognitive screen (HMSE) was used in urban, rural and migrant population. For the tribal population, a modified version of cognitive screen was used. The screen used on tribal population, had to be reliable and valid and as comparable as possible in content, format, and relative level of difficulty to the cognitive screen (HMSE) used in urban, rural and migrant populations. For this purpose a modified version of MMSE was developed. The details are provided elsewhere.[5]

A detailed history of the socio-demographic profile of study population was enquired into.

Clinical evaluation and diagnosis

A score below 24 (out of a possible score of 30) on cognitive screen was considered as a suspect case of dementia and was evaluated for clinical diagnosis. Further 10% of non-demented individuals were also evaluated clinically. The selection of 10% non-demented individuals for clinical evaluation was similar to the process carried out for the purpose of screening for the presence of dementia. In this way every 10th elderly individual was included for clinical evaluation.

The clinical evaluation was carried out by a psychiatrist with the help from an internist and two public health specialists. The subjects were examined for three categories of symptoms: (1) Cognitive or intellectual, (2) functional, and (3) psychiatric or behavioral. An individual was to be confirmed as a case of dementia only after clinical evaluation. The clinical evaluation also meant a revisit to the cognitive screen scores by the clinical team and wherever a difference in scores between the field investigator and the clinical team was noted, the score by the clinical team was taken as final.

For the purpose of this post-hoc analysis, the data of all 2000 participants (total sample) available with us was used. The extraction of data was conducted by another public health expert not involved with the collection of the data. Data on level of literacy and cognitive test were extracted from the total sample. A summary of participant socio-demographic information used in the sample is presented in Table 1.

Results

It is seen that the majority (440/500) individuals in tribal area were illiterate. This was followed by migrant and rural elderly (migrant 373/500; 254/500 rural). [Table 1]. The least number of elderly illiterates (89/500) was found in urban population. A post-hoc Tukey's HSD test did not reveal any significant pairwise comparisons [Table 2]. As expected, groups differed in years of education with post-hoc tests revealing no significant differences for all education group comparisons.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine the influence of level of literacy on dementia in a sample stratified by geography. Results confirmed our hypotheses. Consistent with our previous work, literacy does not seem to be a strong predictor of dementia in our set up.[6] Studies in past suggest a higher prevalence of dementia in groups with less education.[891011] But this does not appear to be so in our study. The reasons for overestimating dementia in less educated could be because of an education effect, which leads to a diagnostic bias, more so in case of mild dementia. Further usage of mini mental state examination without cultural and linguistically appropriate modification may not be the ideal test for diagnosing dementia. This had a bearing in one of the study conducted by us on a tribal elderly population.[7] This assumes importance in a largely illiterate elderly population in India. Studies also point to education effect on vascular dementia. This led the observers to consider whether the association of education with dementia might be due to confounding by cardiovascular disease. This could be a possible explanation, as cardiovascular disease is associated with both education and dementia. Vascular dementia as also Alzheimer's disease is associated with cardiovascular disease.[1213] Studies also suggest that cardiovascular disease is more prevalent in people with less education.[1415] However, these explanations do not seem to work in our settings. If we follow the epidemiological transition model in India, cardiovascular diseases are more common in urban India and urban India is more literate than rural India. Furthermore, dementia in India is more prevalent in urban areas than in rural areas.

Source of Support: The data used in this study was obtained from a research funded by ICMR.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- A calculation and number processing battery for clinical application in illiterates and semi-literates. Cortex. 1999;35:503-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of literacy on neuropsychological test performance in nondemented, education-matched elders. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 1999;5:191-202.

- [Google Scholar]

- Literacy and cognitive change among ethnically diverse elders. Int J Psychol. 2004;39:47-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- A sociodemographic and neuropsychological characterization of an illiterate population. Appl Neuropsychol. 2003;10:191-204.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development of a cognitive screening instrument for tribal elderly population of Himalayan region in northern India. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2013;4:147-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Is dementia differentially distributed. A study on the prevalence of dementia in migrant, urban, rural, and tribal elderly population of Himalayan region in northern India? N Am J Med Sci. 2014;6:172-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Identifying risk for dementia across populations: A study on the prevalence of dementia in tribal elderly population of Himalayan region in Northern India. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2013;16:640-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- The prevalence of dementia and Alzheimer's disease in Shanghai, China: Impact of age, gender and education. Ann Neurol. 1990;27:428-37.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of clinically diagnosed Alzheimer's disease and other dementing disorders: A door-to-door survey in Appignano, Macerata province, Italy. Neurology. 1990;40:626-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Education and the prevalence of dementia and Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1993;43:13-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology, education, and the ecology of Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1993;43:246-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Socioeconomic status and health: How education, income, and occupation contribute to risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:816-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- National trends in educational differentials in mortality. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129:919-33.

- [Google Scholar]